When I first moved down to South-West England, I was intrigued to note that one of the major local commercial property firms, their boards decorating every half-empty high street, was called Alder King. No doubt this is because at some point in the distant past Mr Alder and Mr King got together to form a business (their website is sadly unhelpful on the subject), but in my own private imagination I liked to think that their founder was deliberately trying to invoke a mythical archetype, implying that the cycle of closure, vacancy and opening on the High Street echoed the ancient cycle of death, sacrifice and rebirth, the brief but spiritually charged reign of the sacred king destroyed by the Great Goddess as described by James Frazer and popularised by one of the twentieth century’s best-known English-language poets. No doubt that poet, if he had lived to the 2010s and had seen Alder King’s advertising boards himself, would have thought the same. Rather, he would not just have thought “that’s an amusing coincidence of naming,” as I did: he would have thought it yet more evidence that all of his theories about mythology and prehistory were incontrovertibly, emotionally and poetically true, and that anyone who disagreed with him was probably a contemptible writer-of-prose or Apollonian poetaster with a degree from Cambridge. At least, I assume that’s what he would have thought. I’ve never managed to finish reading his book on the subject, and I’ve threatened to write a blog post about it more than once in the distant past. Today’s Book I Haven’t Read is, as you potentially have already guessed from this introduction, The White Goddess by Robert Graves.

I have a strange relationship with Graves. I’ve been intrigued with him, puzzled by him, almost obsessed with him, since I was a teenager and my English teacher loaned me his own copy of Goodbye To All That, Graves’s infamous autobiography. He wrote it in a great rush to raise cash in the late 1920s after abandoning his final full-time salaried job, and it’s a fascinating mixture of anecdote and recollection dominated heavily by the one great horror at the heart of his life. He had the bad luck to be born into the English upper-middle-class in the mid-1890s: he left public school, and was about to join Oxford University, in the summer of 1914. He became an army officer without even having to try; whilst still a teenager he was a lieutenant, and by the time he would theoretically have been graduating, he had almost been declared dead and was no longer fit for front-line service. Writing your autobiography at the age of 32 might seem somewhat precocious, but the greatest part of Graves’s is purely about his life between the ages of 19 and 23. I hadn’t even realised, when reading the book, that I was reading the now-standard second edition. It was revised by Graves when some thirty years older to take out the more controversial parts: some passages that hugely upset his close friend Siegfried Sasson, and any references to his 1920s attempt at “feminist” polyamory. The original text is a lot harder to find these days, which is no doubt what Graves would have wanted.

I have a strange relationship with Graves, but I don’t think I could ever like him, and certainly I don’t think we would ever have got on if I should happen to somehow go back in time and meet him. He was a mass of contradictions and swirling neuroses. He always insisted he was a poet, but the majority of his income was from novels and biography, books that he himself always derided as “potboilers”. He had a great skill for making stories make narrative sense, though. His retelling of mythology in the Greek Myths has almost become a standard from a literary standpoint, but he picks and chooses sources and details indiscriminately according to his own subjective view of what feels “more mythological”, or in other words, what he feels best fits the story he wanted to tell. Similarly his best-known novel, I, Claudius, is no use at all as history precisely because its point is to fit a narratively-satisfying story on top of a patch of history which Graves felt needed a better explanation than evidence alone could provide. Above all that, he seems to have been a fairly horrible person: misanthropic, homophobic, racist, and with an irrational hatred of anyone with a degree from Cambridge.*

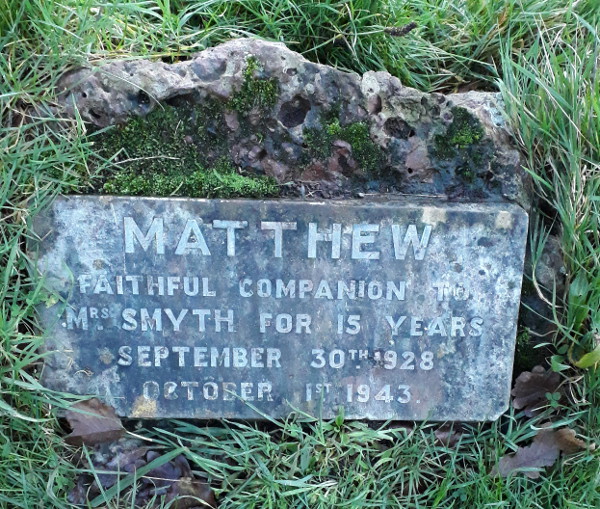

This post, though, is supposed to be a review of The White Goddess and why I’ve never read it all the way through, or, indeed, got more than a few chapters in. Its subtitle is A Historical Grammar Of Poetic Myth, and in it, Graves first gives a very narrow definition of poetry, before explaining why his interpretation of ancient Celtic sources proves that his definition of poetry is correct in an almost geometrically-perfect circular argument. In short: poetry is verse which inspires subconscious terror, fear, and makes your hair stand on end,** because its subject is always male devotion to the all-commanding White Goddess, the triple-goddess of birth, fecundity and death, the goddess who marries her suitor the Alder King for one glorious day before he is destroyed as a sacrifice to her.

All true poetry—true by Housman’s practical test—celebrates some incident or scene in this very ancient story (p20 of the fourth edition)

“Hang on a minute, Captain Graves,” I can almost hear you saying. “I mean that’s fine for you to say, but I’ve written some poetry and it wasn’t about that!”

In that case, according to Graves’ rules, you’re not a poet and you weren’t writing Poetry. To you and me this might indeed sound like nothing more than highest-order gatekeeping, but Graves goes into great effort to explain that it’s true, much of what you might think is poetry just isn’t Poetry by the standards of Graves The Dedicated Poet. Indeed, according to his standards, the English have barely understand poetry at all.

The Anglo-Saxons had no sacrosanct master-poets, but only gleemen; and English poetic lore is borrowed at third hand… This

explains why there is not the same instinctive reverence for the name of poet in the English countryside as there is in the

remotest parts of Wales, Ireland and the Highlands. (p19)

So, Robert, you’re saying that the True Poets are those dashing chaps in flappy shirts like Byron and Shelley and so on, who were always saying they wanted to dedicate themselves to their muses?

This is not to identify the true poet with the Romantic poet. … The typical Romantic poet of the nineteenth century was

physically degenerate, or ailing, addicted to drugs and melancholia, critically unbalanced and a true poet only in his fatalistic

regard for the Goddess as the mistress who commanded his destiny. (p21)

In other words, the only true poets in the world are, really, Robert Graves and a handful of contemporaries he respected (Alun Lewis being one example he quotes approvingly). Others? Sorry, no, whatever you thought you were doing, you’re just not writing poetry by Graves’ standards. The problem I have with this is not just the way it immediately writes off huge swathes of literature, but that this is apparently done so in order to centre Graves, his neuroses and his relationships as the epitome of Poetry, the pinnacle of literature. Graves described himself as a feminist as far back as the 1920s, but his feminism was one in which in reality he was at the centre of things: in which he chose a woman, elevated her onto a holy pedestal, and jealously ensured she stayed there. An emotional masochist, he poured his creative energy into worshipping his chosen muse almost in the hope that she would make him suffer for it. In this sense, his explanation of what makes True Poetry is nothing more than a recapitualation of his personal relationships of the 1920s and 1930s, which he claims to be some sort of universal religious truth. Jealousy itself is elevated to being a vital emotion for the True Poet to have.

What evidence is there, in The White Goddess, that Graves’ inner demons really are the key to both True Poetry and to the ancient mystery religion he claims to be decoding? A dense and cryptic analysis of medieval Welsh poetry, specifically the poem Cad Goddeu, taking it like a set of crossword clues and reordering lines and stanzas in order to produce something that Graves thought made more sense than the original poem. Graves’s “poetic logic” here is much like his logic in writing I, Claudius, or his Greek Myths, or his novel about the life of Jesus: his rewrite of the poem makes a better story, because rewritten it supports his argument, and therefore his argument must be true, because the poem supports it. As a key to understanding Cad Goddeu it is not really anything other than speculation, and certainly not the self-evidently true reconstruction that Graves insists he has produced. To be fair, Cad Goddeu is a famously impenetrable poem and most interpretations of it are little more than speculation, but at least most of the people who attempt to understand it admit that they have no clue what it really consists of.

I said earlier that Graves’ life was governed and steered by the pure luck of being born where and when he was. Similarly, he wrote The White Goddess at just the right time for it to become highly influential: at precisely the time that a new religion was being created in Dorset. As Ronald Hutton has documented in The Triumph Of The Moon, Wicca arose from a seething mixture of British and Irish cultural influences from the late 19th to mid 20th centuries, and The White Goddess, coming at the very end of that period, was one of the most influential on later Wiccan development. Its goddess and its underlying Frazerian story are now widely adopted in modern Paganism, and I’m sure you can find pagans who not only worship Graves’ goddess themselves but believe the ancient Welsh did too. The book has stayed in print for many years, although I do wonder how many of the sold copies have been read all the way through.

So why haven’t I—as of the time of writing—been unable to complete it, despite several attempts? I suspect I’m just too well aware that its basic premise is wrong, or at least, fundamentally flawed. Graves seems to always have been greatly annoyed that academics in both literature and archaeology didn’t think much of it, and that any reviews that did come from academia were generally scathing. He showed it in quite a passive-aggressive way: not only did he write long letters of reply to magazines that gave it a bad review, but some are printed as an appendix to the modern Faber edition. Sadly, they largely show nothing more than his own arrogance and lack of understanding: his insistance that his own outdated knowledge of archaeology and anthropology was far more accurate than that of the professors criticising him. Given I received an introduction to Welsh myth and archaeology at university, I am well aware firstly that much of Graves’ understanding was wrong (even at the time it was written, and it has only grown more wrong since), and secondly that some of his statements make huge leaps in logic and present whole towers of assumption and supposition as if they were solid fact. The entirety of the text rests on sweeping syncretism, with claims such as that the Welsh mythological magician Gwydion is the same character as the Norse god Odin, or that Gwydion’s nephew Lleu Llaw Gyffes is the same character as Hercules and the Mesopotamian god Tammuz. The text resembles a grand conspiracy theory as any similarity between stories and people, however weak, is jumped upon as meaning an equivalence. I opened the book at random to find an example and found this passage, on the ancient Irish poem Song of Amergin:

Tethra [a name mentioned in the poem] was the king of the Undersea-land from which the People of the Sea were later supposed to have originated. He is perhaps a masculinisation of Tethys, the Pelasgian Sea-goddess, also known as Thetis […]. The Sidhe are now popularly regarded as fairies: but in early Irish poetry they appear as a real people. […] All had blue eyes, pales faces, and long curly yellow hair. […] They were, in fact, Picts (tattooed men), and all that can be learned about them corresponds with Xenophon’s observations […] on the primitive Mosynoechians of the Black Sea coast. […] They occupied the territory assigned in early Greek legend to the matriarchal Amazons. The ‘blue eyes’ of the Sidhe I take to be blue interlocking rings tattooed around the eyes, for which the Thracians were known in Classical times. Their pallor was perhaps also artificial—white ‘war-paint’ of chalk or powdered gypsum, in honour of the White Goddess, such as we know, from a scene in Aristophanes’s Clouds where Socrates whitens Strepsiades, was used in Orphic rites of initiation.

There you are: the “real identity” of the mythological Sidhe is uncovered by picking apart random coincidental parallels with things Graves had picked up in his Classical-themed public school education. It’s more like a word association game than genuine historical research. Apologies for editing out the description of the Mosynoechians; it’s impossible to tell from Graves’ account whether there genuinely were coincidental similarities between them and the mythological Sidhe, or whether Graves is being Graves and jumping to conclusions based on the flimiest of matches.

Hopefully one day I will complete reading The White Goddess. The last time I picked it up, I was tempted to live-tweet every time I came to a passage that infuriated me, but soon realised what a thankless and hopeless task this would be after just the second page of the introduction contained the line that Judaism is “a Semitic [religion] grafted onto a Celtic stock”, which is closer to conspiracy-history than anything grounded in fact. I’m certainly not ready to read it just yet. Maybe, instead, I should write something better. Something that is full of open inspirational ideas, not closed and self-justifying ones.

* As someone whose degree is from one of the Ancient Scots Universities, I don’t really have a horse in this race; but I do wonder if he generally thought that any universities other than Oxford were beyond contempt, or if it was just Cambridge specifically.

** This isn’t me colloquialising. He specifically says: a verse is a poem if it makes your hair stand on end if you recite it silently whilst shaving. I can imagine that’s quite handy if you have a dimple or tricky bits around your chin; as a test, it’s attributed to A E Housman. I can’t really imagine Housman agreeing with the rest of Graves’ thesis, and how either of them thought people who don’t shave were meant to separate out poetry and verse is, naturally, not recorded.

Keyword noise: Books I Haven't Read, reading, religion, paganism, Robert Graves, The White Goddess, Goodbye To All That, poetry, history, mythology, fake history, fake mythology, Ancient Britain, anthropology, archaeology, Blodeuwedd, Lleu Llaw Gyffes, Gwydion, Mabinogi, Mabinogion, Cad Goddeu, Cymru, Wales.

Home

Home