As it’s St David’s Day, and the shops are all full of daffodils and Welsh cakes, I thought it might be worthwhile writing something about the history of Wales, possibly even a chain of posts. And the obvious starting point for that is: well, what is Wales?

Back when I was at primary school, we had a few very traditionalist lessons about the history and geography of Britain, and one of the things stated as fact, without meaning or explanation, was that Wales is a principality. Lots of people think this, and lots of people take it for granted, and you still hear “the Principality” used to refer to the country now and again. As you might have noticed, Wales won a rugby match at the Principality Stadium the other day, but that’s named through a straightforward business deal rather than anything more ancient or romantic. But, is Wales a principality? No, not really, not in any meaningful sense. Has it ever been? No, not unless you take “Wales” to mean something rather different to what it does today. But what are the reasons for this misunderstanding? Simply put, this all comes out of the fact that the nature of the Welsh state when it existed does not fit comfortably with what you might call the English pattern of history, the pattern which takes the 19th-century nation state as the ultimate ideal form of political division and judges all historical change against it.

What is a principality, then? Essentially, a monarchy ruled by a prince. There is, of course, a Prince of Wales; but he doesn’t really have very much to do with Wales itself. His vast personal income isn’t from Wales, it’s from the tenants and the business of the enormous Cornwall estate, spread across a huge chunk of south-west England and not really a Cornish affair at all. Much as he sends interfering letters to government ministers behind the scenes, he doesn’t have any formal role to play in government, certainly not any role specific to Wales. The UK is a monarchy in that its monarch signs all its laws (and makes sure any she disapproves of don’t even reach Parliament to be debated), and appoints its government, but the Prince of Wales doesn’t have any say in the matter. Laws passed by the Senedd are signed off by the Queen in the same way that laws passed by the Westminster Parliament are signed off by the Queen. The Prince of Wales? Sits around, running his business empire, slowly curdling with frustration knowing that he has reached retirement age with the whole world seeing him as a sort of semi-comic understudy. Wales is clearly not a principality in any functional or meaningful sense.

Was Wales ever a principality, in reality? Well, parts of it were. Only, though, if you go back a rather long time. Even then, as I said, Wales does not fit very well into the English pattern of history, because it followed a very different history to England.

Everyone in England thinks of England as a unitary, unified, single state that has been around for a literal eternity. That has, indeed, been the truth for a very long time. England came together as a single unified state well over a thousand years ago, but it did so largely for one very specific reason: to define itself in order to save itself. England became a unified single country in response to “the Danelaw”, the control of most of the country by Danish and Norwegian settlers who almost wiped out the English kingdoms that resisted them. The surviving anti-Dane English aristocracy rallied and unified, producing a single kingdom of England with its centre of gravity forever fixed firmly in the South. France to some extent has a similar history: the power of the early Frankish kings around Paris rose significantly just as they had to defend themselves from Danish incursions up the Seine. In Ireland, the Norwegians ended up founding a new capital city, and in Scotland the Norwegians ruled a huge (if marginal) chunk of the modern country for about four hundred years or so. I’m aware, by the way, that I am simplifying swathes of historical argument here, thousands and thousands of pages of academic debate into one paragraph for a surface-skimming blog post. Real historians: please don’t write in. Wales simply didn’t face the same Scandinavian pressure as the rest of Western Europe. The Danes and Norwegians sailed round the coast, and gave names to many of the important coastal bits (step forward Swansea, Anglesey and Fishguard), but don’t seem to have settled in the concentrated, forceful, focused strength-in-numbers way that they did around the mouths of the Seine, the Liffey or the Humber.

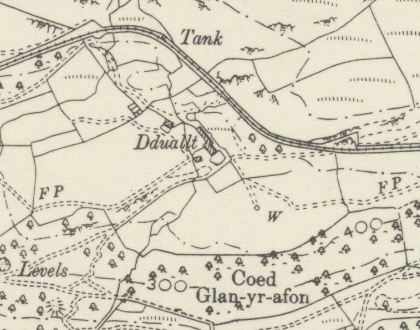

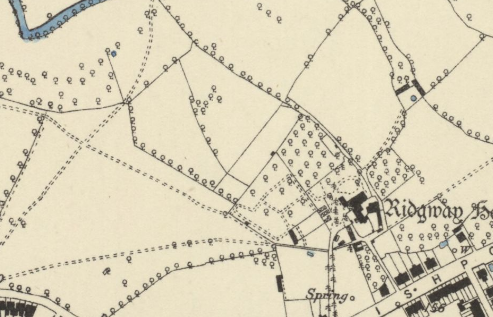

There’s also the economic determinism argument about Welsh history. Put simply: it is that the geography of Wales is distinctly different to that of England in a way that, in the pre-modern period, made it hard to unify. There are still constant complaints in Welsh politics that North-South travel is too hard and that Cardiff is too distant from Holyhead to rule it effectively or to understand its needs. There is often a call that the fact there is no North-South rail link entirely within Wales is somehow a failure of Welsh politics or of English centralism, skipping over the fact that it is a fundamental problem with Welsh geography, and that the only entirely-within-Wales links from South to North were for their whole existence extremely marginal links.* Similarly, the A470 links Cardiff with Llandudno but it is in no sense a coherent and sensible route, just a mixture of cross-country links all coloured in with the same pencil on a map so that somebody could indeed claim that there is a single South-to-North road.** The point here is that, in an age when everyone depended on food grown pretty close-by for their regular staples, and when local kings depended on a personal warband of big burly followers as an army, it was just too difficult in a country like Wales to gather together sufficient force from your own core estates and project that force into a different part of the country, to do that in any sort of way that stuck. Each of the small medieval Welsh kingdoms has this core area which could act as the motor of a pastoral economy: Ynys Môn for Gwynedd, for example, or the upper Severn valley (as pictured here a few weeks back) for Powys. Each also has a belt of less hospitable land protecting it from the others. It therefore shouldn’t be surprising that the history of medieval Wales is a history in which for a short time one of these kingdoms was able to assert itself over some or all of the others, but such assertions barely lasted more than a single reign. Or so the theory goes, at any rate; we should always be suspicious of such straightforward determinism, if you ask me. Note, too, that these were kingdoms, with kings. Not principalities.

When all those Danes who had settled at the mouth of the Seine invaded England very successfully in the eleventh century, they stopped short of invading Wales. Or, rather, their kings stopped short of invading Wales in a controlled and centralised way. However, rich and important landholders were allowed to invade Wales on their own account; and as long as they still recognised the English king as their overlord, they were effectively sovereign in their Welsh estates. This means that later medieval Wales was much more like medieval Germany in its political structure than anywhere in England or Scotland: a patchwork of relatively small states, each independent, quite martial, at each other’s throats from time to time, but most generally recognising a kind of “imperial” overlordship. It’s in this period that the Welsh leaders’ titles start to slip downwards, from king to prince. Over the course of this “marcher” period—and again I am enormously oversimplifying here—the tendency was for both types of state, both Welsh-ruled and English-ruled, to both coalesce and grow more accepting of the King of England’s overlordship. By the thirteenth century the family of the kings of Gwynedd had reached the point of taking over all of the other Welsh-ruled microstates—about two-thirds of the land area but only half the population, because the invading English lords had naturally headed for the economically best bits—and at this point they started to use the title “Prince of Wales”. Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd was promptly rubbed out very thoroughly by the English, with most of his family aside from one brother who Anglicised his name,*** moved East, and settled down as a quiet provincial landowner on the border of Kent and Surrey. His territory became something in-between, not part of England, but not as independent of England as the Marcher lords, with strict rules to prevent the Welsh from holding any sort of political power unless they could very definitely be trusted.

So that was the Principality of Wales: most of the Welsh-speaking people didn’t live there, and it wasn’t really ever ruled by a Welsh prince. It lasted until Tudor times, when Henry VIII shut down the last of the Marcher lordships and integrated all of Wales into his kingdom, with the aim of removing almost all Welsh political distinctiveness. It then disappeared, except in name. Wales is not a principality, and huge chunks of the modern country were never part of the principality that arguably did exist.

Will Wales ever be a principality? Well, never say never. The UK today is clearly on a path towards fragmentation; there is a tremendous energy in the UK’s extremities towards fission of the country into multiple separate parts. You don’t have to travel far in Wales right now before you see a pro-independence banner, sticker or graffito.

Although the breakup of the UK is probably now inevitable, the exact form that it will take is still impossible to predict. It’s a fair bet, though, that when Wales does become independent, it will be the first time in history that a single unified and unitary state of Wales has existed; and secondly, that it will not be a monarchy of any form. Republican sentiment is already much higher in Wales than elsewhere in the UK, and this is likely to increase as support for Welsh independence increases. Wales is not a principality, and Wales is not going to be. Cymru am byth!

* Firstly, the Manchester and Milford Railway. As its name suggests it was originally meant to be a lucrative main line linking the ever-churning Satanic mills of Manchester with the Atlantic harbours of West Wales. It ended up as a sleepy rural byway linking Carmarthen with Aberystwyth. Secondly, there was also the Mid-Wales Railway which linked Brecon to Newtown via Rhyader; from Brecon you could get to either Swansea via Neath, or to Newport or Cardiff via the vertiginous Brecon and Merthyr Railway. With either of these routes, to truly get North you had to either reverse once or twice and head up the coast to Caernarfon and Bangor, or give up on the whole avoiding-England lark and go the other way via Oswestry.

** It must be a South-to-North road because of its number. If it was a North-to-South road its number would start with a 5, because Llandudno is north of the A5 and west of the A6.

*** From Rhodri ap Gruffudd to Roderick Fitzgriffin.

Keyword noise: Cymru, Wales, history, hanes, hanes Cymru.

Home

Home