The spooky season

So, a trip to a particularly impressive tomb

It being the end of October, tonight is Halloween, or nos calan Gaeaf for any Welsh-speakers reading. I’m not in costume and I haven’t decorated the house, but I did think it might be nice to have a suitably Halloween-themed post on here. Rather than go with ghosts, ghouls or goblins, I’ve gone with a tomb, a relatively interesting one, so much so that English Heritage have designated it a listed building. It’s a place I only found out about a few months back via an Instagram post by Kate of Burials and Beyond. As it’s only a couple of miles or so from where I grew up, my immediate reaction was “why have I not heard about this place before?” So yesterday, I went down there with my camera.

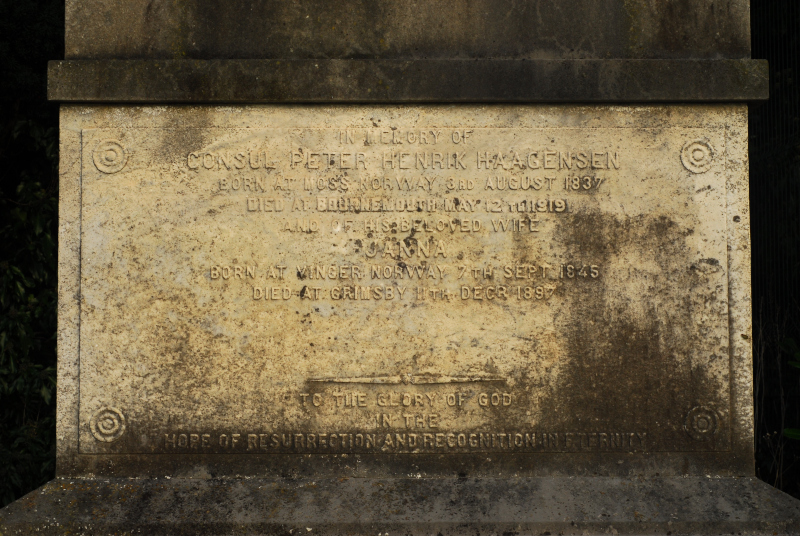

This is the Haagensen Memorial, carved from a single block of marble and desposited on a plinth in one corner of a Lincolnshire cemetery. Underneath it is a vault, the tomb of the Haagensen family. That’s them—well, most of them—in the statue: Janna Haagensen being escorted into heaven by an angel, whilst her grieving children try to drag her back to earth. The marble treestumps below almost look like the fingers of a hand, twisting around and trying to grasp her too.

Janna Hagerup was Norwegian, born in Vinger in 1845. At the time Norway was not, strictly speaking, an independent country. Although self-governing, it was part of the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway, ruled by the King of Sweden and with its foreign policy controlled by the Swedish government. Janna married Peter Haagensen, a ship-broker, and in 1868 they moved to Grimsby to handle the English side of the family business. Three years after moving to Lincolnshire, the Swedish government appointed Haagensen as consul for Sweden-Norway in Grimsby.

When Janna died in 1897 after a history of respiratory problems, Peter was—we can assume—heartbroken. Although the family lived in a large villa close to Grimsby town centre, by the junction of Bargate and Brighowgate, Peter purchased a cemetery plot out in the village of Laceby, a few miles away. The reason? He wanted to build a grand vault for the family, and (we can assume) the Grimsby cemetery authorities didn’t like the idea.

The memorial doesn’t just consist of the grand sculpture of Janna and her children. Below it, a marble-lined vault was excavated, with mosaic floor, and with spaces for both Janna and Peter’s coffins. The steps to the vault were closed with an ornate iron gate at ground level. You can see it today, firmly locked shut.

The vault is still there in good condition below, though. On infrequent occasions, Laceby Parish Council open the vault to visitors, and you can go down and see the finely-carved marble, the mosaics, and the tombs of Peter and Janna themselves.

Peter died 24 years after Janna, and was himself interred in the vault following a Norwegian-language funeral.* Norway had become fully independent in 1905, but I’m unclear whether Peter had remained consul of either or both countries—or, indeed, had retired from the roles completely.

What happened after Peter’s death, though, is a little unusual. The tomb was by far the largest memorial in Laceby cemetery; indeed, it was almost certainly the largest memorial to one family anywhere in the area. In the 1920s, therefore, it became something of a tourist attraction, with people from Grimsby, Cleethorpes and even further afield in Lincolnshire taking days out to Laceby to view the memorial. A tea room opened in the village to serve the tourist trade, and the Haagensen Memorial became a picture-postcard subject. China replicas were made, and Laceby tradesmen started up weekend jobs peddling them to the tourists, to take home and put on their mantelpieces. For a few years between the wars, the Haagensen Memorial was a local tourist hotspot. Earlier I doubt it could have happened, due to the difficulty of reaching railwayless Laceby, but in the 20s it was easy to take a charabanc tour out to the village to see the sculpture. I’m not sure how long the tourist boom lasted, but I would assume the outbreak of the Second World War put an end to the last dregs of the traffic.

Norway and Sweden both still maintain small consulates in Lincolnshire today. Norway’s is in Flour Square, Grimsby, near Lock Hill; Sweden have moved theirs out to Stallingborough.** The Haagensen Memorial is still maintained and preserved by Laceby parish council, but it’s not a tourist attraction any more. Indeed, when I was there yesterday to take these pictures, I was the only person in the entire cemetery. Hence, I suppose, why I’d never heard of it until this year: it’s almost forgotten. Still, let’s remember Peter and Janna Haagensen and their grand tomb. Maybe tonight, their souls will walk abroad.

The historical info in this post was largely gleaned from the official Historic England listing of the memorial.

* I’m going on the information I uncovered. What that means in practice, particularly at the time period we’re talking about, is a bit unclear, but you can assume it means some form of Danish-Norwegian.

** Ironically, the Swedish consulate in Lincolnshire is located on Trondheim Way. Presumably they couldn’t find a street named after a Swedish city.

Home

Home

Newer posts »

Newer posts »