Test shots

Or, looking up at the sky

A couple of weeks ago now, I mentioned that I’d been outside and pointed the camera up at the sky to see what happened. It’s about time, I thought yesterday, that I tried to actually see if I could make the photos that resulted useful in some way.

This is all down to a friend of mine, Anonymous Astrophotographer, who I won’t embarrass by naming, but who manages to go out regularly with a camera and a tripod and even without a telescope produce beautiful pictures of the Milky Way and various other astronomical phenomena. I asked them what their secret was. “Nothing really,” they claimed, but gave me a bit of advice on what sort of software to try a bit of image-stacking and so on.

I thought, you see, that given that The Child Who Likes Animals Space’s telescope doesn’t have an equatorial mount, it would be pointless to try to attach a camera to it. You can, after all, visibly see everything moving if you use the highest-magnification eyepiece we’ve got at present. Equally, surely it would be pointless just to point my SLR up into the sky? Apparently, not, Astrophotographer said. The trick is to take lots of shots with relatively short exposure and stack those together in software. The exposure should be short enough that things don’t get smeared out across the sky as the Earth spins—anything over 20 seconds is probably too long there—and the number of shots should in theory even out random noise in the sensor, stray birds, and so on.

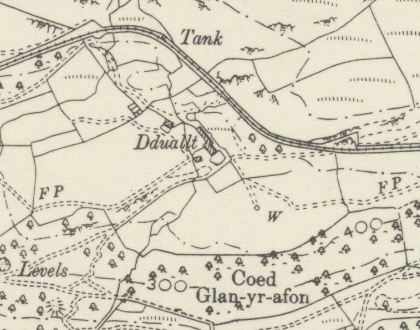

As a first attempt, I thought, there’s no point trying to get sight of anything particularly special or impressive, so I pointed the camera to a random fairly dull patch of sky and see what happened. You can click to see a larger version.

This is an arbitrary area in the constellation of Draco. In the middle you have Aldhibah, or ζ Draconis, with Athebyne (η Draconis) over on the right and the triangle of Alakahan, Aldhiba and Dziban over on the left. The faintest stars you can see in this image are about mag. 7.5, maybe a little fainter, which is a bit fainter than you could see with the naked eye even in perfect conditions. This image has been adjusted slightly to lower the noise; in the original you could just about persuade yourself you could see mag. 8 objects, but they were barely distinguishable from noise. The Cat’s Eye Nebula (NGC 6543) and the Lost In Space Galaxy (NGC 6503) are both theoretically in the picture, in the lower left, but they’re not visible; the former can just about be spotted as a faint pale patch very different in shade to the noise around it on the original images, if you know exactly where to look.

Here’s the handle of The Plough, with the stars Mizar and Alcor together in the middle. This one really doesn’t look much at a small size, but if you click through you can see how well the camera captured the different colours and different shades of starlight. Again, the darkest things visible here are about mag. 7.5. The Pinwheel Galaxy is right in the middle of the lower centre, but at mag. 8 or so doesn’t come out of the noise at all.

What do I need to do to make things better? Well, for one thing, the seeing wasn’t actually very good on the night I tried this. As I said in the previous post I had to give up fairly quickly due to cloud. What I hadn’t realised, until I saw the photos, was that faint clouds, lit up by moonlight, were already rolling in well before it became obvious to the naked eye. Trying some photography again on a clearer night would definitely be a start. Secondly, my SLR is pretty old now, dating to the early 2000s. The sensor is, compared to a more modern one, fairly noisy at low light levels. I’m not going to rush out and buy a new camera tomorrow, but I do suspect that if I did, the attempts above would get quite a bit better.

Home

Home