For a few months now, I’ve been threatening to start writing a long series of blog posts about the railway history of South Wales, starting in Newport and slowly radiating outwards. The question, of course, is how to actually do that in a format that will be interesting and engaging to read in small chunks; and, indeed, for me to write. The “standard” type of railway history comes in a number of forms, but none of them are particularly attractive to the casual reader. Few go to the point of setting out, to a random passing non-specialist reader, just why a specific place or line is fascinating; just what about its history makes it worth knowing about. Moreover, not only do they tend on the heavy side, they are normally based either on large amounts of archival research, large amounts of vintage photographs, or both. Putting that sort of thing together isn’t really an option for me at present, especially not for a blog post.

So why would I want to write about the railways of the South Wales valleys in any case? In general, if you’re a British railway enthusiast, you probably think of the South Wales valleys as a place where GWR tank engines shuffled back and forth with short trains of passengers or long trains of coal. If you’re a specialist, and like industrial railways, you might remember it as one of the last areas where the National Coal Board still operated steam trains, at places such as Aberpennar/Mountain Ash. There are two things, though, that you probably only realise if you’re a specialist. Firstly, if you include horse-drawn railways and tramways, the South Wales railway system was the earliest and densest complex railway network in the world. Horse-drawn railways are often completely overlooked by enthusiasts, for whom railways started with the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester line in 1830. Partly, I suspect, because unlike later periods there aren’t many good maps or any photographs of most of the horse-drawn railways of this country. Although horse-drawn railways do appear on tithe maps, in most cases they are not very clearly marked and resemble a road more than anything else.

Secondly, the 19th century history of the growth of the South Wales railway network was intensely complex and entangled, and the later domination of the area by the GWR was by no means a foregone conclusion. Through the 1850s and 1860s there were a number of factions at work: on the local level, horse-drawn lines trying to modernise and make their railways part of the national network; newer steam-operated lines each serving a single valley and without any scope for a broader outlook; and nationally, the large London-based companies trying to gain “territory” and a share of the South Wales industrial traffic. In 1852 two directors of the London & North Western Railway, Richard Moon and Edward Tootal, said:

[A]ll the Narrow Gauge Lines [standard gauge] of South Wales are at present detached: & divided into separate & small Interests:- Again they are at present at War with the Broad Gauge.

(memo to LNWR board quoted in The Origins of the LMS in South Wales by Jones & Dunstone)

I’ll come to the reason why Moon and Tootal were investigating the railways of South Wales in a later post; but that, hopefully, sets the scene a little. South Wales didn’t become a GWR monoculture until, paradoxically, after the GWR itself ceased to exist. Through all of the 19th century, South Wales was a maze of twisty little railways, all different, many of them with very long histories.

All of which, if you’ve read this far, brings us on to a fairly ordinary-looking back lane behind some houses, in a fairly ordinary suburb of Casnewydd/Newport.

You’ve probably guessed this is actually some sort of disused railway. It is; but it’s a disused railway that, paradoxically, is actually still in use. This is the trackbed of the Monmouthshire Canal Company’s tramway; its exact date of building is a little unclear but it was started around 1801 and open for traffic in 1805.

I’ve written about the Monmouthshire Canal Company before, as a good chunk of the Crumlin Arm of its canal has been semi-restored, albeit not in a navigable state. The canal was built in the 1790s, following the valley of the Afon Ebwy/River Ebbw down as far as Tŷ Du/Rogerstone where it cut across north of Newport to reach the Wsyg/Usk.

The canal’s enabling Act of Parliament permitted anyone who wanted to use the canal (within a few miles radius) to build their own horse-drawn feeder railway linking them to the canal. This included the Tredegar Ironworks, in the Sirhowy Valley; the only sensible way they could reach the canal, however, was to build their railway all the way down along the Sirhywi until reaching the confluence of the Ebwy and Sirhiwy in Risca. The canal company built a matching line, roughly parallel to their canal for much of its length but running around the south side of Newport. The picture above is part of this line, near the modern day Pye Corner station.

Above I said that paradoxically, this is a disused railway that is still in use. The reason for that is: a line built for horses to draw trains at walking pace is not exactly suitable for use by powered trains at much higher speeds. A secondary reason is that in many cases the new “rail roads” were the best road in the area, became heavily used by pedestrians, and started to have ribbons of houses built along them in the same way that public roads do.

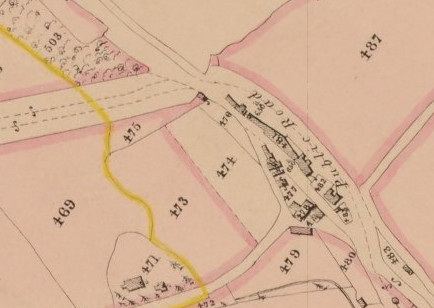

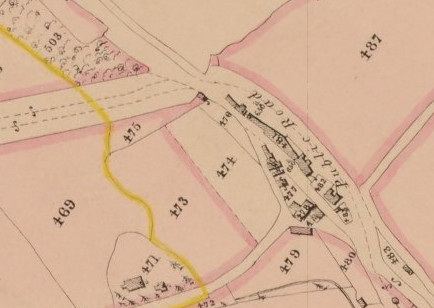

This is the tithe map for the photo shown above, from around 1840. As you can see it’s hard to see the difference, in this map, between the railways and the roads; but a “public road” has already been built around the other side of the buildings that have grown up along the railway, so that people don’t have to walk on the railway to get to them.

When this map was made, the railway had already been using steam engines for around fifteen years or so. Not long after, the company decided its trains needed a better line of route here, so a new line was built, parallel, only a few tens of metres to the west. That line is still in use today as Trafnidiaeth Cymru’s Ebbw Vale Line, although it’s seen many changes over the years.

I was going to segue into the later railway history of the Pye Corner area at this point, because there’s plenty to discuss. Indeed, as far back as the mid-1820s there was already a railway junction there, and on the tithe map above you can see the second line striding off to the left of the map. It’s technically no longer a railway junction. There are still two routes here, but they come together and run parallel rather than actually joining. As this is already turning into something of an essay, though, that will wait for a later day.

Keyword noise: Cymru, Wales, Casnewydd, Newport, hanes, history, hanes lleol, local history, rheilffordd, railway, railway history, trains, Pye Corner, Great Western Railway, Monmouthshire Canal, maps, tithe maps.

Home

Home