Original footage

In which we consider moving to the mountains

The other day I was rather pleased to discover, on YouTube, a documentary from the 1970s that I’ve known about for a while but had never before seen. The Campbells Came By Rail is a documentary about the everyday life of Col. Andrew Campbell.

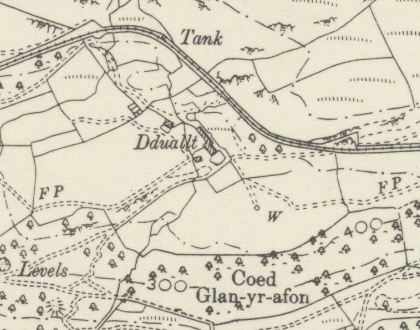

Colonel Campbell had a long and successful career in the Black Watch, largely overseas, policing the crumbling corners of the British Empire. Coming out of the Army in the early 1960s, he became county solicitor for Merionethshire (as was). At auction, he bought an equally-crumbling manor house in the northern fringes of the county, which he had fallen in love with at first sight. Its name was Dduallt.

If you’re a regular reader—or paid attention to the title of the documentary—you may well be ahead of me here. Dduallt,* when Campbell bought it, had no vehicular access, but it was alongside the Ffestiniog Railway. At the time, the Ffestiniog were not operating services over that stretch of track; so the Colonel bought a small Simplex locomotive and had a small siding built alongside his new house. The railway let him park his car at the nearest station, Tan y Bwlch, and run himself up and down by train.

The documentary shows him picking up his loco and a brakevan from Tan y Bwlch and heading off up the line to show the filmcrew round his home, describing it as part of his normal daily commute from the county council offices. Off he heads, past the cottage at Coed y Bleiddiau, up to his own Campbell’s Platform, where he puts the train away.

Unlike a modern documentary, you get to see all the detail of the Colonel putting the train staff into a drawer lock, working his groundframe, and then a demonstration of how to use an intermediate staff instrument,** including a spin of the Remote Operator dynamo handle to make sure the section is clear and the instruments free.***

As I said above, when Campbell moved into Dduallt, the railway wasn’t operating over the stretch of line past his house. By the time the film was made, that part of the railway had reopened to traffic, and it must have been difficult on a busy summer day to find a space in the timetable for the Colonel to run down to Tan y Bwlch in the daytime. Further north, the railway was rebuilding a couple of miles or so of line that had been drowned by a reservoir, and Colonel Campbell had provided invaluable help. For one thing, he allowed the railway’s civil engineering volunteers to use one of his buildings as a hostel provided they helped restore it, which they did complete with a large London Underground roundel sign on one wall. For another, he was a licenced user of explosives, so was called out each weekend to blow up rocks along the path of the new line. If you look in the background of the documentary you can see a couple of wagons carrying concrete drainpipes are sat in Campbell’s siding, no doubt waiting to be used on the new line.

Eventually, Campbell did get a roadway built to the house, zigzagging steeply up the side of the vale, but only in the last few months of his life. He died in 1982, the same year that the Ffestiniog Railway completed its 27-year reopening process. The Ffestiniog went through a number of significant changes in the early 1980s, and the loss of Colonel Campbell was one of them. He is still an iconic figure to the railway, though, so watching the documentary was a fascinating opportunity to have some insight into who he was, what he looked like, what his mannerisms were. In particular, the upper-class Englishness of his accent startled me somewhat, given he was on paper a Scot. That, I suppose, is what being an interwar colonial Army officer turned you into. There is a whole thesis that could be written on colonialism and the Ffestiniog, given that it was funded in the 1830s by Irish investors and re-funded in the 1950s by English enthusiasts—and considering the long, bitter and quixotic arguments the railway had with Cymdeithas Yr Iaith Gymraeg in the 1960s and 1970s, arguments characterised by a tone of disingenuous legalistic pedantry on the railway’s side. It’s certainly far too complex a topic to be summarised within this single blog post. In the documentary, Campbell was very clear that after ten years of living at Dduallt he still felt himself to be an outsider; indeed, he gives you the feeling that he didn’t think he would ever truly belong to the land and to the house in the way that his farming neighbours did.

The Ffestiniog Railway is a very different place now, with a very different attitude to the local community. Dduallt has changed hands a few times since Campbell’s death, most recently just in 2020 after sitting on the market for some years. Its final price was a bit over £700,000, less than the sellers wanted but somewhat more, I think, than when Colonel Campbell picked it up at auction. It’s in rather better condition now, of course, not to mention rather more photogenic when shot on a modern camera. Apparently, if you go there (and the Ffestiniog will start running trains past it again next month) you can still see parts of the aerial ropeway that linked the house and its station back in the 1970s.

The documentary is certainly a moment in time, and that time has now moved on. Nevertheless, if you know what the railway is like now, it’s a fascinating watch. If you don’t, maybe it will entice you to visit. It’s certainly worth it.

* The famous-but-controversial railway manager Gerry Fiennes once said that the best way to pronounce Dduallt was by sneezing, which is cruel but more accurate than pronouncing it as if the letters were English.

** Technically speaking it’s a “miniature electric train staff”.

*** The Remote Operator handle and indicator is a Ffestiniog peculiarity, developed to enable the railway to operate with unstaffed token stations and traincrew-operated signalling equipment. There is more information about it in this video about one of the Ffestiniog’s signalboxes.

Home

Home