As it’s nearly Hallowe’en, I thought it might be time to post a creepy story. And this is a true creepy story. I posted it originally on my Tumblr, six years ago, as an account of something that happened to K and I when The Children were both still only crawling and we took them away on holiday for the first time, to a holiday cottage on a farm in North Cornwall. It happened a few weeks before I wrote it down, more or less exactly as it is set down here, in the middle of the night just before we were due to leave. I haven’t edited the originally, so “about a month ago” should be read as “September, 2014”.

This is not a ghost story. It has no climatic ending, no plot and no dramatic arc. It is, however, something of a paranormal story. Moreover, the reason it has no plot and no ending is that it is a true story. The reason I’m writing it down is because it was strange enough to merit remembering, and I wanted to write it down before its strangeness was corrupted and faded away.

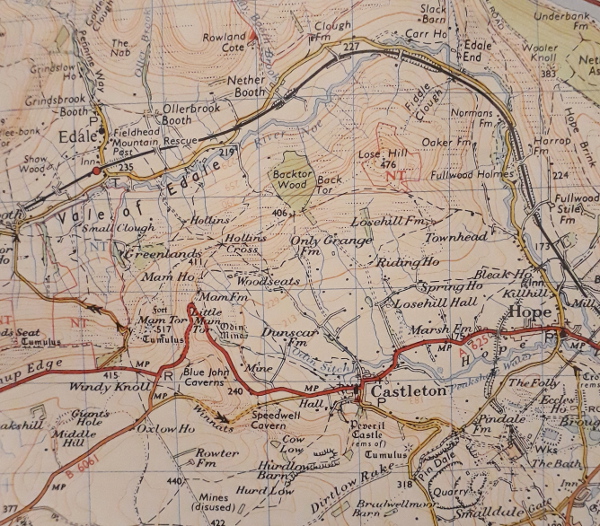

About a month ago, my partner K and I took our 10-month-old twins away for their first holiday. They had reached the stage of crawling, climbing, and taking an interest in everything they saw, but had not quite mastered their first steps or their first words. Thinking it best not to travel too far away for a first holiday, we hired a cottage on a farm in North Cornwall, in the wedge of land between the River Camel and the sea, the landscape that is famously the home of both King Arthur and the North Cornwall Railway. The cottage was, to be frank, more like a modern bungalow than a stereotypical Cornish cottage; but it was indeed on a small, slightly ramshackle farm, and was surrounded by beautiful countryside. It overlooked rolling hills, small ancient fields divided in haphazard fashion by twisting raised hedges and sunken holloway lanes. It was a beautiful, disorienting landscape: looking out from the picture windows of our cottage’s front room, I was convinced I was looking north or north-east until careful correlation of maps and hedge-lines persuaded me we actually faced southwards. A small ravine led the eye gently towards the distant lights of the nearest town, but otherwise there were no landmarks in sight, not even a church tower or a sign of the nearest village. Not being able to find north is unusual for me: I’m normally fairly good at orienting myself. When I was a child, I read lots of Enid Blyton books in which the characters always wake up on the first day of a holiday and, forgetting they’ve gone on holiday, have no idea where they are. To me, this is an entirely alien concept.

We stayed for a week, Saturday to Saturday as is the custom, and greatly enjoyed ourselves; this isn’t the story of our holiday, but suffice to say we had a wonderful time, and returned to our cottage each night to settle down cosily on the sofa. Not having a TV at home, we enjoyed the illicit treat of snuggling up, sleepy babies alongside us in their sleeping bags, quietly watching inane programmes about home redecoration and suchlike.

I wondered a few times just what the night sky looked like on a clear night there, given how dark our cottage felt with the lights out, but most nights, at least when I remembered, the sky was overcast and no stars could be seen. On our final night, though, I needed to go outside, and saw what seemed a perfect black sky, scattered everywhere with starlight pinpricks.

We were cleaning up the kitchen that night, after the babies had settled down to bed, and I said to K, my partner, that we should go outside to look at the stars. It would be romantic, I thought. Outside, though, a mist had started to drift in. Towards the south, the stars were still on show; towards the north the sky was black, and the mist was already thick enough to be noticeable over the hundred yards or so across the farmyard, between our cottage and the farmhouse. “Can we go inside?” said K, nervously. Not to get ahead of things, but she admitted later that, just before this, just as the mist had started to drift around the farm buildings, was the point at which she had started to feel anxious about our surroundings.

We went to bed as normal, hoping that we might get an uninterrupted night of sleep - an unusual treat for us at the moment, as it’s rare that our daughter doesn’t wake up wanting a cuddle and a small drink. In the strange surroundings of our holiday cottage, much darker and quieter than our city home, both babies had tended to go to extremes, either sleeping soundly all night, or waking and refusing to settle back down to sleep.

In the middle of the night, I woke. There was screaming from the babies; loud, urgent screaming from both of them. Where was it coming from, though? I knew instantly, as if the idea had been pushed into my head: the babies were outside. We had left the windows open, I thought, which was why we could hear them; the babies were outside, in the garden, crawling around on the grass surrounded by fog, and I had to go outside and rescue them. It was the one thought in my otherwise terrified mind: I had to go outside. I couldn’t find where I was, though. I stood, next to the bed, and whirled around, arms out, trying to find a wall or a door.

Before I had left the room my mind had cleared slightly, and I realised there was no way the babies could have left the cottage, or even have climbed out of their cots. As I still kept trying to work out which direction the crying babies were in, though, I suddenly realised that something, something nearby, was trying to make me leave the cottage.

Staggering a little, I made it out into the hallway, and quickly closed all of the doors off to the other rooms. Going to the desperately crying babies, I tried all the usual methods of settling them back to sleep: a drink of water, a tight hug, soft words. Nothing worked. I was trying not to think about the dark feeling I had that something else was inside the building, trying to help the babies relax, but the babies were still clearly very upset, still crying, definitely not going to go back to sleep on their own.

One at a time, I hurriedly carried them back into our bedroom, so that all four of us could settle back down together in bed. K has also started to wake, and held them close to her. “Have you shut all the doors?” she mumbled.

“Yes,” I replied.

“I’m scared,” she said. “I feel like there’s someone else in the cottage.”

Rationally, I knew I had locked the doors. The only way in was through a door with a bolt on the inside, which I had bolted before bed. So why did we both suddenly feel that someone or something else was inside? Why had I felt it was trying to trick me into going outside?

I quickly went, trembling slightly, into the hallway. Open the living room door. Flash the light on. Nobody there. Despite what I had thought earlier, the windows were firmly closed and locked. Into the kitchen: nobody there, the windows closed and the door still bolted.

Back to bed. “There’s nobody else here,” I said, “and the doors are all shut.” The babies were slowly calming, drifting back to sleep making quiet whimpering sounds. Slowly, me hugging our son and K hugging our daughter, we drifted back to sleep.

The next morning the mist had gone, the cottage was itself, and it almost felt welcoming again. We were glad to leave, though. I don’t think we even dared discuss it, hardly, until we had loaded the car, had our final chat with the farmer and his wife, and were driving the car under the horse chestnut tree that shaded the farm’s gates, and off down the long dead-end lane that took us back towards the Atlantic Highway. We had no idea, no idea at all, what we had felt, or what could have been influencing us. What struck both me and K, though, was that without discussing it - without even being able to - all four of us had apparently woke up with great distress in our minds. Obviously we don’t know what the two babies were actually thinking; but they were most certainly not their usual awake-in-the-night selves, and nor were K and I. K had been, as I said above, nervous that something was approaching before we’d gone to bed, but she didn’t mention a word of it until the next morning.

I’ve searched for information, since we came home, about possible haunted mists and rural panic attacks associated with that area. I have a vague memory, after all, that the word “panic” originally meant a specifically bucolic terror, after Pan himself. Nothing I’ve found, though, has been connected to that part of the country. K suggested that panics can be caused by ultrasonic noises, which could be a plausible and non-supernatural explanation for us all feeling the same terror. At root, though, I don’t think this is ever going to be fully explained, or fully explainable. All I can tell you is that: it did happen, exactly as I’ve told you above.

Keyword noise: Cornwall, holiday, panic, paranormal, ghost stories, fog, mist, cottage, The Children.

Home

Home