Black comedy

On death, and its absurdity

Almost a year ago, give or take a week or two, my dad died. I wrote, a few days later, about the experience, or at least part of it. Starting from being woken in the middle of the night by a phone call from the hospital, and ending with myself and The Mother walking out of the hospital, wondering what would happen next. I scribbled it down a few days later, after I had had a couple of days to process it, but whilst it was still relatively fresh in my head. The intention, naturally was to write more about the experience of being newly-bereaved, the dullness of the bureaucracy, of everyone else’s reactions to you, the hushed voices and awkward moments. Of course, none of that ever got written. Nothing even about his funeral. Much of it has now faded. I was thinking, though, now that I’ve relaunched this blog once more, maybe I should go back, go back over those few weeks last October, and try to remember exactly what it did feel like.

What first struck me at the time, though, is how darkly comic it all seems. I touched briefly in that previous post about some aspects of the bureaucracy, how hospital staff, when it happens, silently upgrade you to being allowed to use the staff crockery and unlimited biscuits, at the same time as quietly closing doors and shifting barriers around you to try to stop everyone else noticing there has been a death. Afterwards, though, it continues. The complex arrangements of paperwork that must be shuffled round to make sure the burial is done legally. The way customer service agents on the phone switch into their “condolences” voice, when for you it’s the fifth call of this type in a row and you just want to get them all over with. On that note, at some point I really should put together a list of how well- or badly-designed different organisations’ death processes are (the worst were Ovo, whose process involved sending The Mother a new contract that they had warned us would be completely wrong and should be ignored, but that they had to send out).

The peak of dark comedy, though, has to be everything around the funeral arrangements themselves. Right from our first visit to the funeral home, a tiny bungalow just next door to The Mother’s favourite Chinese takeaway. Like probably most funeral directors in the UK now, it used to be a little independent business but was swallowed up by one of the big national funeral chains when the owner retired. Because of this you can’t phone them up: all calls are routed via some impersonal national call centre. They have two people locally staffing the office, and they work alone, one week on, one week off. You have to admit that that’s a pretty good holiday allowance, but it is for a job in which you spend most of your time alone, apart from potentially with a corpse in the next room to keep you company. At the time of course, we knew none of this, so just decided to pop in to the office as we were passing on the way back from some other death-related trip.

Now, if I had written all this down at the time, or at least made notes, I’d have been able to recount exactly what was so strange about the little office. Such a hush inside, almost as if something had been planted in the walls to soak up sound. The cautious, tactful way the woman behind the desk asked how she could help us, and in my mind, the dilemma of how exactly to say. “We need to bury someone” just sounds that little bit too blunt, but equally, I didn’t want to dance around in circumlocutions all afternoon. She sat us down and took us through all the details, each one laid out in a glossy catalogue sent by Head Office. None of the prices, of course, were in the catalogue, and looking through I found it almost impossible to tell which ones were meant to be the cheap ones and which the expensive. Indeed, anything as vulgar as money was carefully avoided for as long as possible, and when it really had to be mentioned, the undertaker wrote down a few numbers on a piece of paper and passed it over to us, rather than do anything as shocking as say a price out loud.

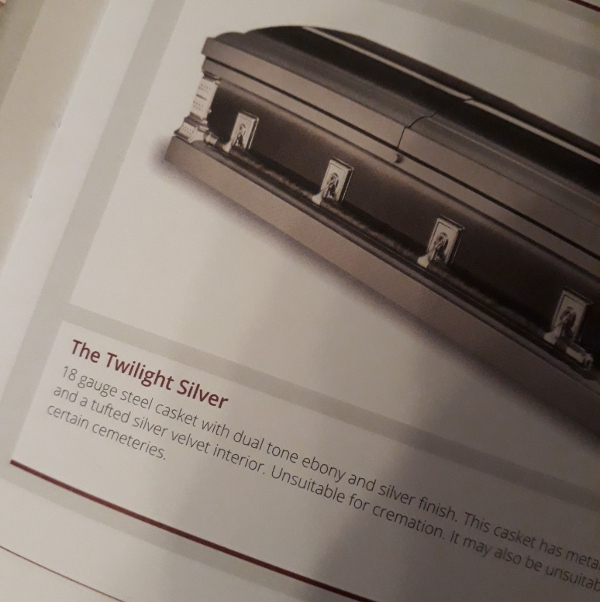

The thing that I really couldn’t stop laughing at, though, I didn’t notice until after we took the brochures back to The Mother’s house. It was a small, three word sentence in the details of one particular coffin in the coffin catalogue.

Yes, you can have a solid steel coffin if you like, in chunky thick blackened-finish steel. At a rough guess the steel in that coffin must weigh somewhere around 60 or 70 kilograms, so you might want to warn the pallbearers first. What made me laugh, though, is the thought that maybe, until they put that line in, someone somewhere didn’t realise that maybe it wasn’t a good idea to cremate a sheet steel coffin. Maybe they didn’t even realise until they opened the oven and found it, glowing a dull red still, all stubbornly in one piece, the contents turned to charcoal instead of burning.

Home

Home