Beating the bounds

On how unchanged our landscapes can sometimes stay

Recently I’ve been reading Viking Britain: A History by Thomas Williams, so far at least a very good and modern history of the Viking Period in the British Isles, evoking what we know, what we don’t know, and particularly, what experiencing the Vikings may actually have been like, and what they may have thought. In particular it is very good at making clear which stories are likely true, which are likely not true, and which were assembled to make something that may have resembled a form of poetic, literary truth, even if in truth things did not happen exactly as the sagas and chronicles describe.

This blog post isn’t about that book as a whole, though, if nothing else because I haven’t finished reading it yet. This post is about a small section in one of the introductory chapters, translating a land grant from 808 AD, from the King of Wessex to the brethren of a church in Bath. The following is my own edit, picking my favourite parts from William’s translation and the version published online in the Electronic Sawyer Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters.

First from the swine ford up along the brook to Ceolnes’ Spring; along the hedgerow to Lutt’s Pit; then on to the edge of the coppice; along the edge to the road; along the road to Ælle’s Barrow; down to Alder Coombe; along Alder Coombe and out to the Avon; along the Avon to the swine ford.

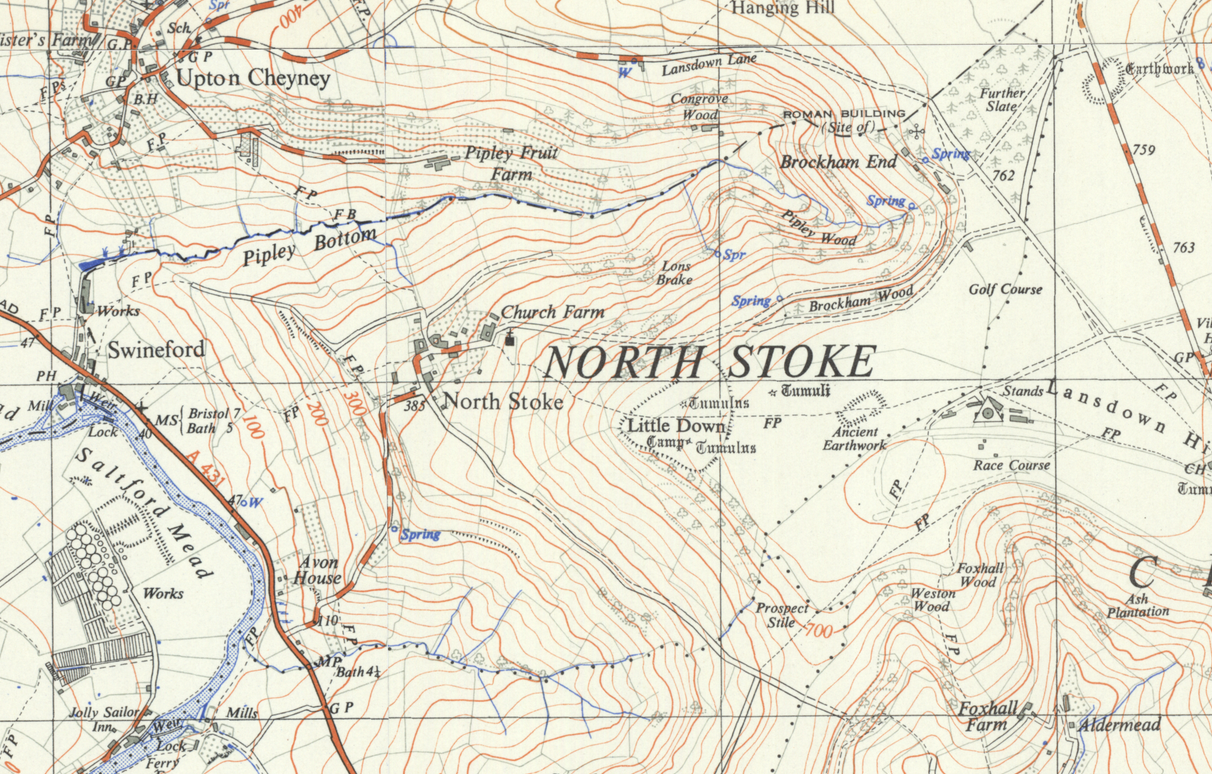

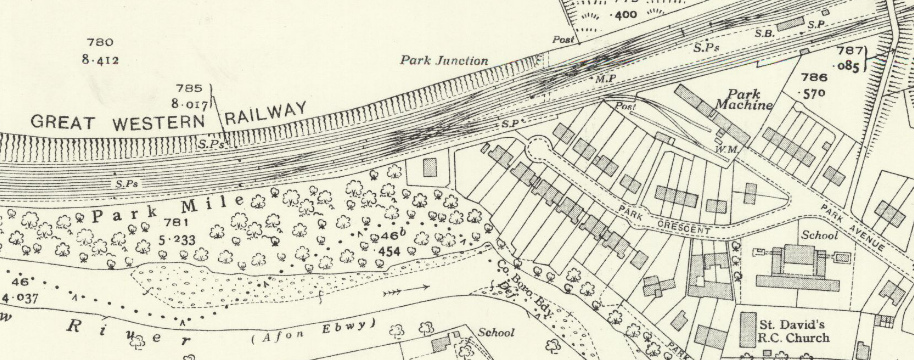

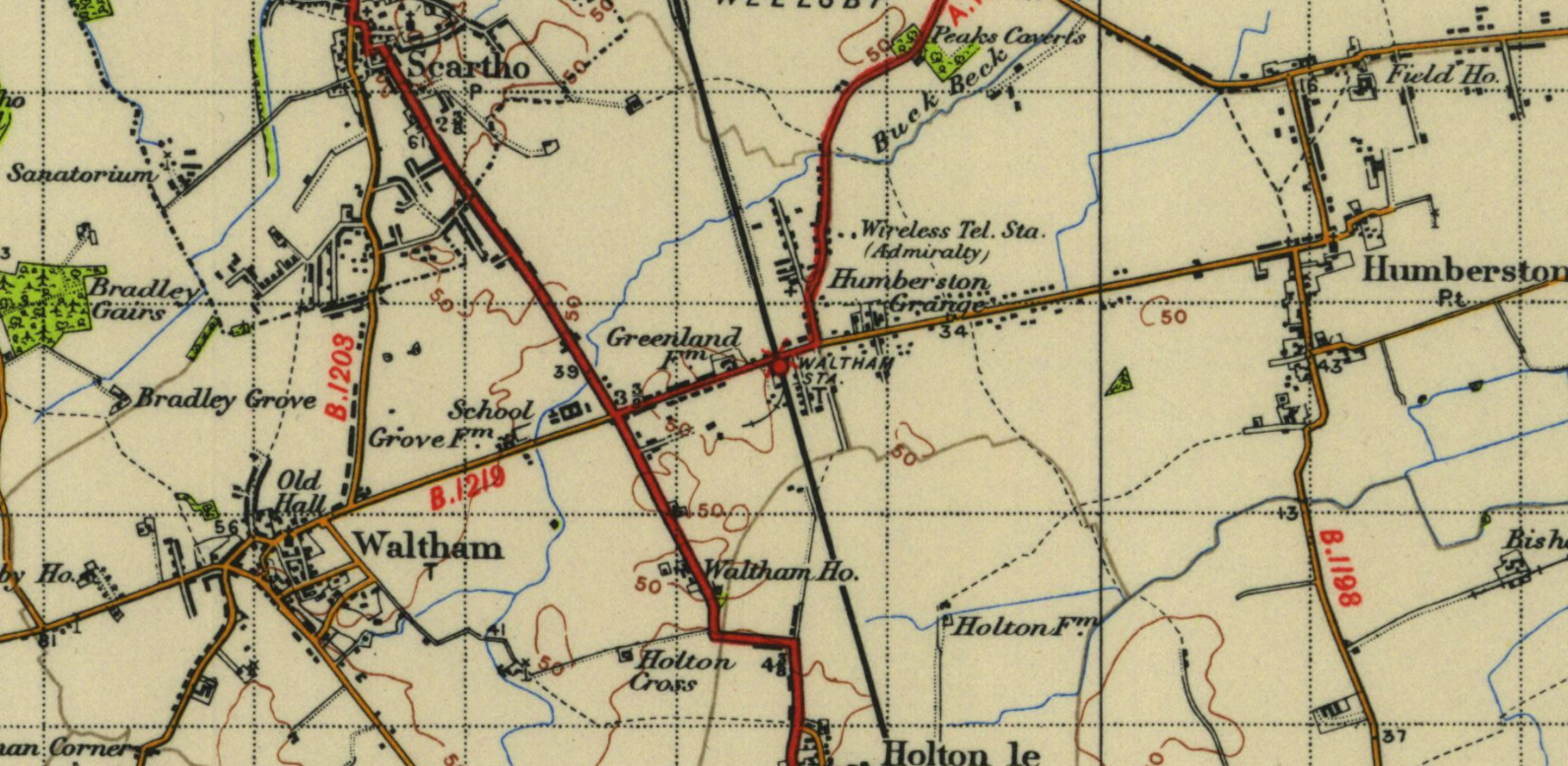

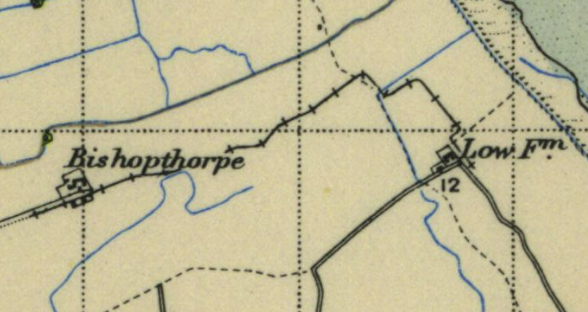

“The Avon?” you might be thinking if you’re from Bath or Bristol. “The Swine Ford?” I pulled out the maps, and found Swineford, where the Avon Valley downstream of Bath starts to widen from a few hundred yards wide to a mile or two. I used to travel through it daily on the train, to and from work, looking out for the deer in the morning fields. And the land grant, as described, is very clearly still largely the modern boundary of North Stoke parish, although it gets a bit hard to trace up towards Lansdown and near the racecourse. This map is from the 1950s, partly for aesthetics and partly for copyright reasons, but the parish boundaries haven’t really changed much since then.

Swineford, after all, is still Swineford. The brook leading up to the spring must be Pipley Bottom; and there are a number of springs up in Pipley Wood. On Lansdown it is now hard to trace, as the road pattern has changed, the racecourse has been built and there are any number of prehistoric earthworks that could be Ælle’s Barrow; but Alder Coombe must be the small wooded valley that runs down to the river near Avon House.

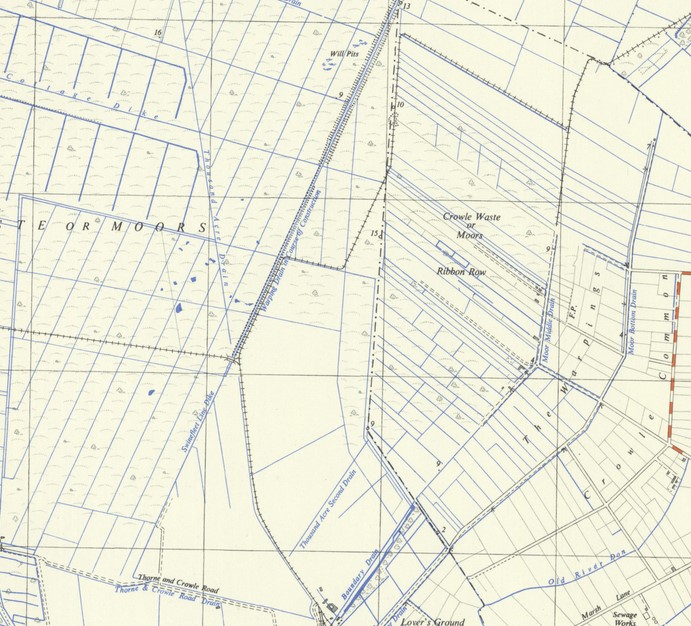

It’s strange to think that this line on the map, this little patch surrounding one small village, has not in essence changed very much for around 1,200 years. No doubt there are many parishes across England where the same applies—not so much in Wales due to the rather different early medieval history of that country. In Lincolnshire, for example, parish boundaries still sometimes follow the line of Roman-period roads which were landmarks in Saxon times but today are little more than farm tracks or lines on a map.

I’ve never explored North Stoke, just seen it many times from a train window. Maybe, as the year comes in and the days grow lighter, I should try exploring the ancient boundaries of some of the places around me. Just to see what I can still trace.

Home

Home

Newer posts »

Newer posts »