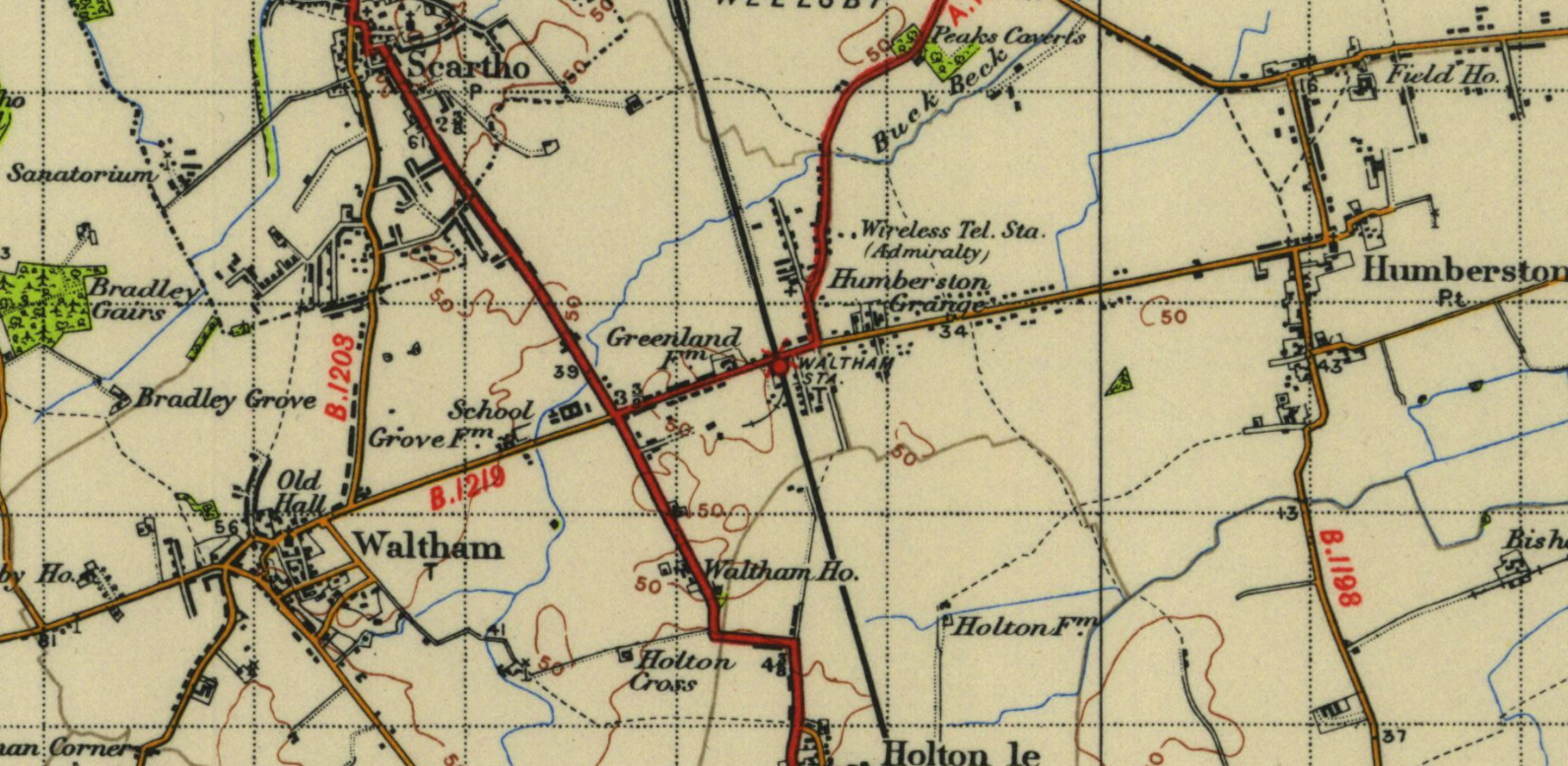

In search of more historical things to write about on here, I remembered something I had once randomly happened across when I was a teenager. A memorial, in the next village, to a man who had randomly died there. So yesterday I went out, bent over against the January wind, to search for it, find it, photograph it and write about it. Having only a vague memory from years ago, I was fully prepared to have to spend hours searching for the thing. In the event, though, I couldn’t miss it.

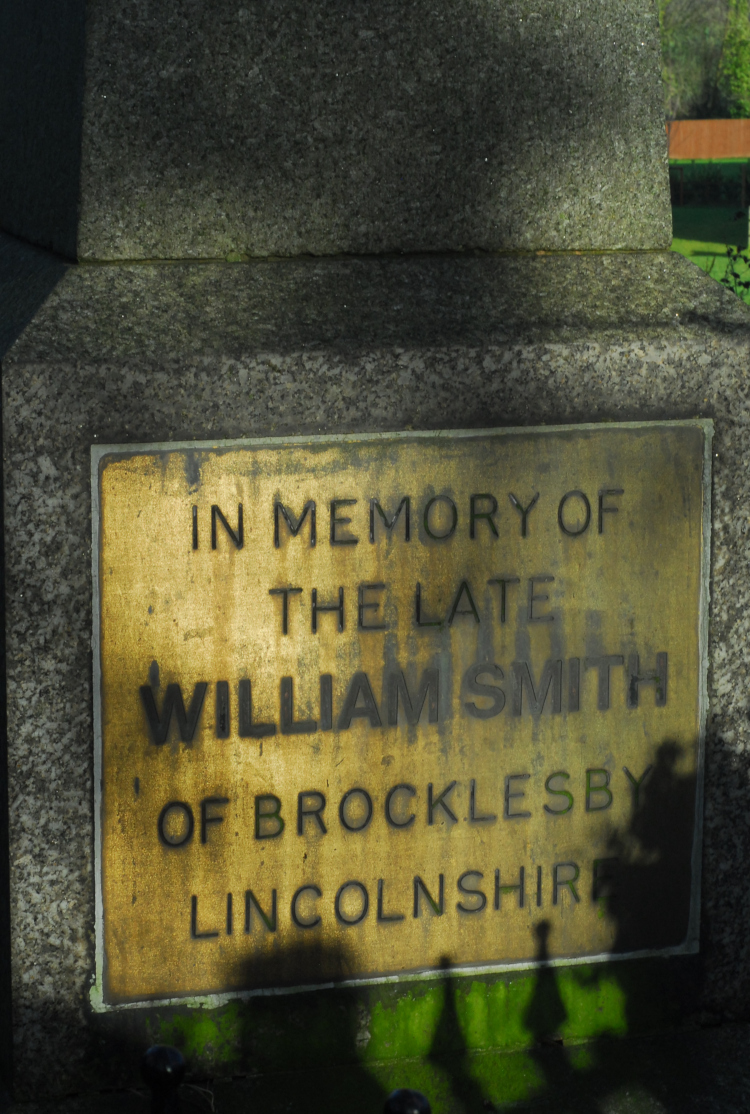

This is the Huntsman’s Obelisk, a mid-19th-century granite memorial at the side of a quiet country lane. It commemorates the death of William Smith, a huntsman thrown from his horse in the 1840s.

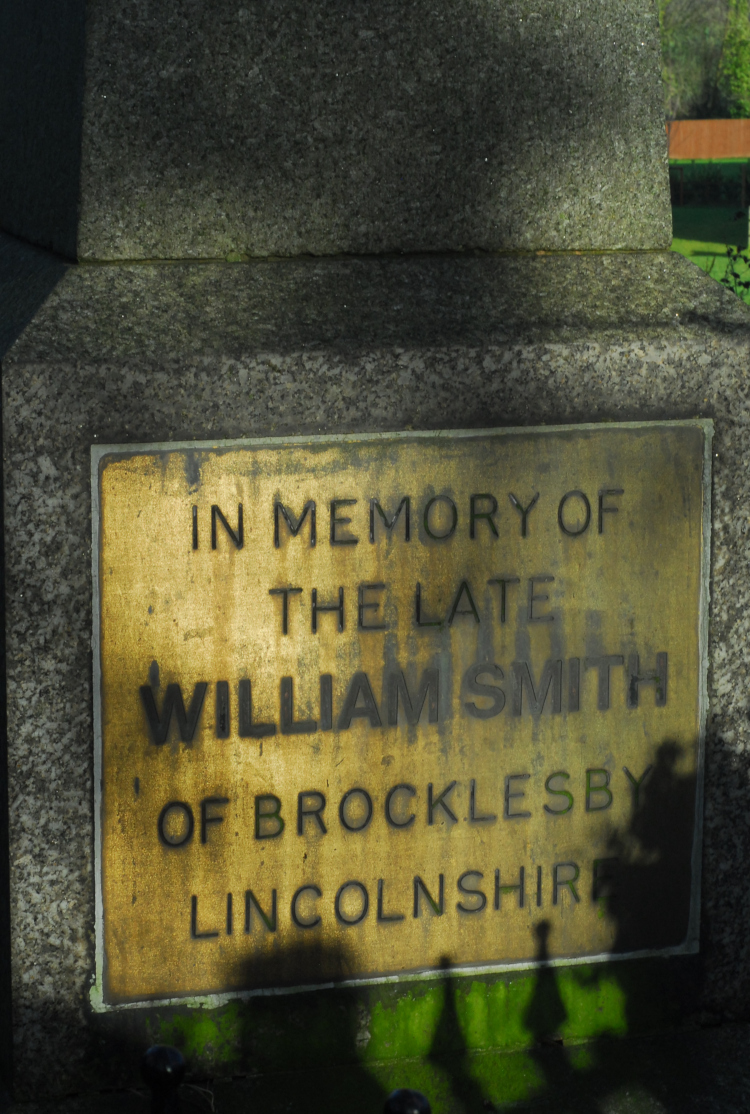

In memory of

the late

William Smith

of Brocklesby

Lincolnshire

If you’re a cynic like me, you’re probably also looking at that plaque and thinking that typeface looks rather too modern for an 1860s plaque. Indeed, I think it is modern, definitely postdating the monument being listed in 1986. Around the other side, there’s another plaque, explaining the story of why the monument is here.

THIS MONUMENT was erected by his many friends, as a token of their regard, and to mark the spot where WILLIAM SMITH,

huntsman to the Earl of Yarborough, fell on the 11th of April 1845.

His gallant horsemanship, and his management of hounds, in the kennel and in the field, were unsurpassed.

His horse, falling over a small leap, whilst Smith was cheering on his favourite hounds, he was thrown on his head, and from the injuries, he then received

he died on the 16th of April 1845 at the house of his friend, Richd Nainby of this village esquire, by whom the site for this memorial

was given on the 6th day of April 1861.

Whatever your views on this font here, the wording, not to mention abbreviations like “Richd“, seems authentically Victorian. The reason I’m so sure that the first plaque is a modern one is that the listing entry of the monument doesn’t, at the time of writing, mention it at all. It does, though, say that one of the two plaques “contains an impressive 22-line ode to Smith by CHJA”. There’s no sign of anything like that on the monument today, and there are only two plaques mentioned in the listing. The first one above, therefore, must be later than 1986.

It’s a shame a 22-line Victorian ode in memory of a dead huntsman can disappear to be replaced with modern typography, not that I have any particular affection for hunters. Quite the reverse, in fact; I just don’t like to see history eroded. Without interpretation, most people who pass by and look at the obelisk will no doubt not even notice one of its plaques has been replaced. I wonder, too, what the ode originally was, and quite how awfully sentimental it was.

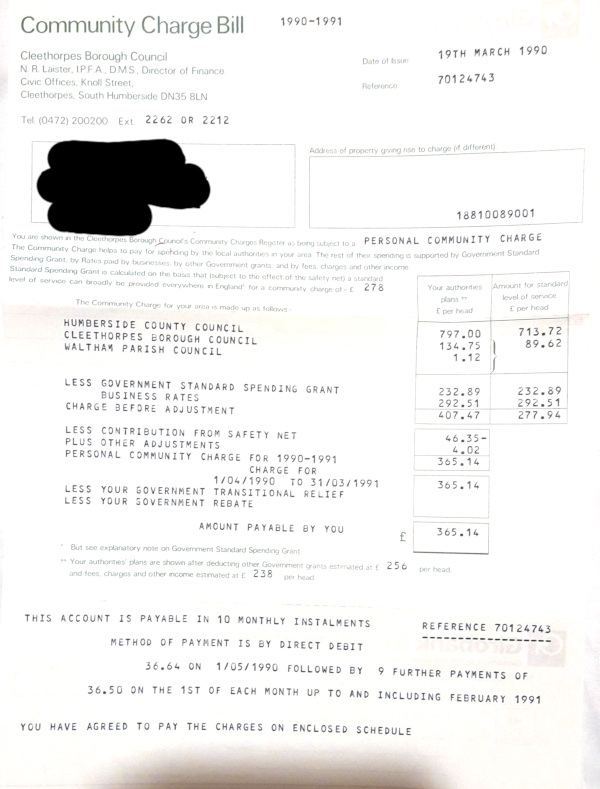

The other thing that occurs to me—and I think has always occurred to me about this memorial—is the length of time between the death and the erection. Sixteen years, and a lot had happened in those sixteen years. The Earl of Yarborough died the year after Smith, quietly on his yacht rather than out hunting. He had been chairman of the Great Grimsby and Sheffield Junction Railway, which opened to traffic* in 1848 and began the process of changing Grimsby from a medieval village into a modern industrial-scale fishing port. Moreover, nationally, Britain was changing radically. I wonder, when the obelisk was erected by a small crowd of men, sadly remembering their friend from a few years before, how much they thought about the world around them changing; how much they no doubt hated it.

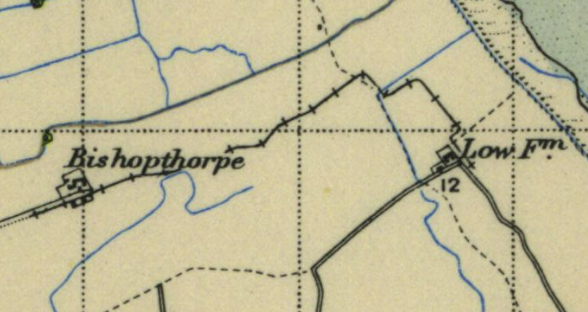

Opposite the obelisk is St Helen’s Church, a lovely little building in your stereotypical overgrown churchyard. Even when I was growing up St Helen’s no longer had its own priest; the Rector of Waltham would hold an early service in their own church each Sunday, dash over to Barnoldby to hold one there and then back to Waltham for the main Eucharist. I’ve never been in, but its churchyard certainly looks like it would be worth exploring.

The Marrises would have been in their 30s when Smith died. I wonder if they remembered the event, or if it had passed them by.

I turned away and walked up the snowdrop-fringed lane, and out into the open fields to be blasted by the wind again.

* No train nerd would forgive me if I didn’t footnote that, by the time the railway opened, the company had become part of the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway, its lines becoming part of the famous Manchester-Grimsby “Woodhead Route”

Keyword noise: Lincolnshire, North East Lincolnshire, Barnoldby, death, memorial, history, local history.

Home

Home