What rhymes with...?

Or, a trip up a mountain

What do you do on a random Saturday with zero plans? Walk up a mountain? What an excellent suggestion, thank you! So yesterday morning I headed off for a gentle amble up to the summit of the Blorenge, the mountain that stands over the valley of the River Usk opposite the Sugar Loaf, and separates the urban environs of Blaenafon from the rural tranquility of Abergavenny and Crickhowell.

I say “a gentle amble” because it’s not a particularly strenous walk. It’s not like the sort of mountain where you park your car at the bottom and hike up a path so steep you’re almost too scared to come down again. The road over the mountains north from Blaenafon isn’t that much lower than the summit, only about eighty metres or so. The walk, therefore, is essentially a cross-moorland ramble more than anything else. Still, it’s definitely a good way to spend a morning.

When I thought of posting this, I was intending to turn it into something hugely informative: a long story full of history, geology, packed with information about the mountain. Unfortunately, I couldn’t quite work out how to get into it. It turned into something dry and meaningless, without flavour, when I wanted to write something evocative, something that would make you really feel you were on the mountain alongside me. What I do have, though, are pictures.

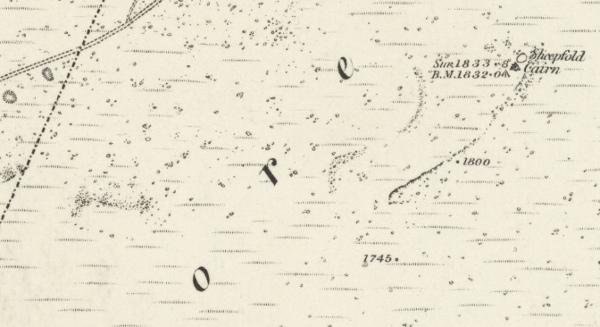

I started here at Keepers Pond; at least, that’s what it’s called on the signs. The Ordnance Survey map calls it Pen-ffordd-goch Pond—the head of the red path. Older, Victorian-era maps call it Forge Pond. The whole area around the Blorenge is filled with ancient industry: pits, hollows, old quarries and old mining tips, joined up by tracks that were once horse-drawn railways. Nowadays Keepers Pond is busy with wild swimmers, canoers and paddleboarders. The only ancient industry I found was one length of Victorian railway rail.

Despite all its ancient industry, the Blorenge now is a quiet place, a place where the loudest sounds are of songbirds. There are many hikers, but they walk silently, conversations blown away by the wind. In the distance you can see all the way to the Severn Sea, in the far distance the coast of Somerset, but on Saturday the skies were grey, the clouds low, and sea, sky and distant land all merged into one continuous blue-grey palette.

At the summit, naturally, there’s a trig point. On the ground, though, unmarked, a second benchmark was carved. An old one, by the look of its shape. Possibly, it is the benchmark labelled on an 1880s map as 1,832 feet.

To the north, at first, the view was lost in cloud, leaving just impressions of a valley. Then, slowly, as I returned back to the car, it started to open up again. The valley of the Usk, the Black Mountains and the Sugar Loaf. The grand vista stretched before me, before the cloud came back down again once more.

Home

Home

Newer posts »

Newer posts »