Flatlander

Or, a trip to the Crowle Peatlands Railway

There are so many preserved and heritage railways in the UK—there must be something around a hundred at the moment, depending on your definition—that it’s very difficult to know all of them intimately, or even to visit them all. It doesn’t help that still, around 55 years after the “great contraction” of the railway network in a quixotic attempt to make it return to profitability, new heritage railways occasionally appear, like mushrooms out of the ground after rain.

Which is why, a few weeks ago, I decided to pop over to Another Part Of The Forest and visit one of the very newest: the Crowle Peatland Railway. It’s still only about three and a half years since the CPR first started laying track; only about ten years since the railway’s founders first conceived of the idea, and less than a year since passengers have been able to ride on it.

The CPR was built to preserve the memory of a very specific, industrial type of narrow-gauge railway, one that is associated more with Ireland than with Britain. The Crowle Peatlands are part of one of the largest lowland bogs in England, the Thorne Moors, on the boundary between North Lincolnshire and South Yorkshire. Drained from natural wetland by the engineer Cornelis Vermuyden in the late 1620s, from the mid-19th century the area started to be mined for peat, with a network of railways bringing the peat from the moors to factories at their edges for processing and transshipment. For many decades these railways used horse haulage, but from around 1950 the peat company switched to petrol and diesel locomotives.

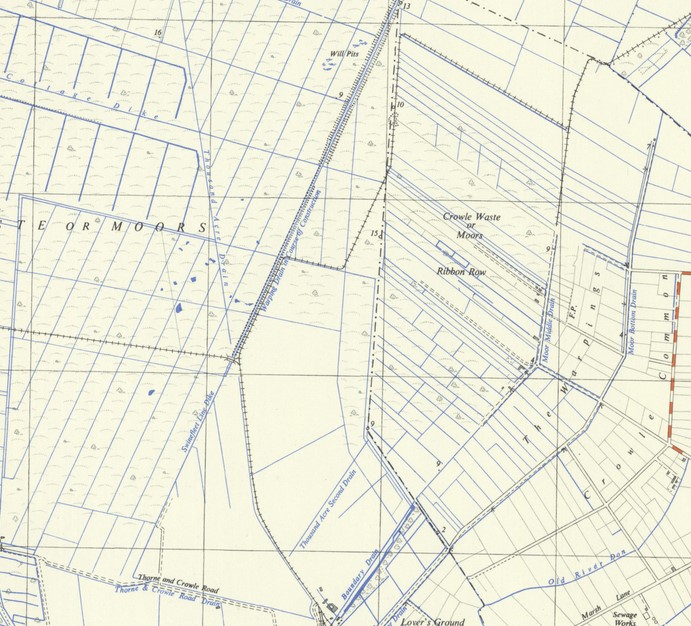

This map shows the Moors at around the time the railways started using locomotive power: you can see the lines of railways across the moors, following the drainage canals, making sharp, almost-hairpin corners. Even in the 1980s there were still between 15 and 20 miles of narrow gauge railway across Thorne Moors, remaining in use until peat mining ended around 2000; the newest locomotive on the railway was bought new as late as 1991.

The preserved railway is in the area shown on that map as “Ribbon Row”, west of Crowle, reached along a narrow, dead-straight lane across the flat landscape of the Moors. As soon as you are outside the town, it feels disconnected, remote, outside the normal world entirely. As I drove, in my mirrors, I saw a young deer crossing the road behind me.

To date, the railway has a café with very nice home-made cake. a maintenance shed, and a straight line of track stretching out across the moor. The shed is full of the sort of small diesel locomotives that worked on the moors from the 1950s onwards—and also, a Portuguese tram.

I think the loco on the left is Schöma 5130 of 1990; the diamond-shaped plate is the builder’s plate of Alan Keef of Ross-on-Wye, to mark the loco being rebuilt in the late 1990s with a more powerful engine, which you can see here.

The newest loco to run on the peat railways was named after a retired member of staff in the early 1990s, shortly after it was built.

The railway’s other locomotive is a Motor-Rail Simplex built in 1967 and abandoned around 1996 due to worn bearings.

It’s a nice little engine, much less powerful than the newer ones, but I’m not sure what I think of lime green as a locomotive colour.

On a map—if it had made it onto any maps yet—the railway would no doubt appear as a dead straight ine; but on the ground it follows gentle curves and undulations. At 3ft gauge the track feels wide for a narrow-gauge line, especially given the small size of the powered trolley that takes you out onto the moor. On my run I was the only passenger, with a driver and guard to look after me, as we pottered out along the track, surrounded by wildflowers pressing close up to the track, fat bumblebees buzzing close to the car as we went.

No stations; no platforms; no sidings. No signals other than a fixed distant sign warning that the track will run out soon. Just a single line of track, which stops. Back we go; with me and the guard having the best view this time, although I tried to make myself thinner and not block the driver’s line of sight.

That photo shows practically the whole railway, with the shed visible in the distance. We trundled back in, feeling far faster than the handful of miles per hour we were actually doing. Retracing our steps, back to the yard.

The Crowle Peatland Railway isn’t somewhere I’ll be going back to again that soon, because for now, I’ve seen all there is to see. But it is a nice little place to visit, a reminder that everyone starts somewhere, and that sometimes a railway is just a stretch of line running out into a field. It’s open and running trains about one weekend a month at the moment, and it’s worth visiting for the cakes. Or, indeed, if you just want to be out in a landscape where the horizon is straight as a ruler, and there are few noises beyond the wind blowing the grass.

Home

Home

Newer posts »

Newer posts »