Moments Tact Is Important

In which we know when not to start speaking

Moments Tact Is Important, number one: When introducing your partner to the person you fantasise about during sex.

“And this, darling, is the person I fantas… oh, bugger.”

A homage to loading screens.

In which we know when not to start speaking

Moments Tact Is Important, number one: When introducing your partner to the person you fantasise about during sex.

“And this, darling, is the person I fantas… oh, bugger.”

In which there is a flood, and the flood sirens stay silent as per specification

A few months back now, the famously low-quality Local Council decided to spend lots and lots of money on flood warning equipment. They picked the most advanced flood warning system they could find, and erected enormous, giant-scale towers around the town, with large banks of speakers on top. They published maps of the town, with circles spattered over them, looking rather like those 1980s maps of nuclear blast radius,* so everyone knew which areas would be able to hear the flood sirens.

And now, with the worst rainfall for years, and roads closed or barely passable all over town, what have the flood sirens done? Absolutely bugger all, of course. Because that’s not the sort of flood they’re designed for. They’re to warn us against floods from the river defences failing, or the New Haven** bursting its banks. Neither have happened, although the New Haven looked to be within a few inches of a breach yesterday. Instead, we have flooding here because the Council don’t bother cleaning the drains out, so all the rainwater puddles on the roads.

* Talking of nuclear blast radius, who was the “psychic” who “predicted” that Hull would be destroyed by a nuclear attack in 1981? I really must look him up some time.

** It’s the “New” bit of the sluggish stream running through town, because it was cut in the sixteenth century.

In which we notice that Google Maps is a step back in time

Google Maps has recently, it seems, spread its high-resolution satellite coverage over much more of the UK than before.* It now covers, for the first time, this part of the world.

I spent quite a while looking at various places around the area, seeing what I could spot; and it quickly became obvious that even though Google have only uploaded the pictures recently, they’re not new pictures. I asked around the office for advice, and as far as we can tell, the pictures are four or five years old. The new cinema next to the Boating Lake is, on Google, an empty field. My car isn’t anywhere to be seen, because I didn’t have a car back then. Wee Dave spotted his own car, outside his old house.** Various other buildings haven’t been built, or are still there on the pictures having been knocked down a few years ago. It’s intriguing; and I can’t help wondering just how Google picks its areas to upload, and if it’s been sitting on these tiles since Google Maps UK first started.

* Thanks to Martijn for mentioning it, otherwise I wouldn’t have noticed

** actually, he spotted “the one that the missus wrote off a few years ago”

In which we discuss an artist of invention

The other week, I wrote about W Heath Robinson, and how I first discovered him: illustrating the children’s books of Norman Hunter. He wasn’t as good for the stories, though, as a later illustrator, who is much less well known. His name is George Adamson.*

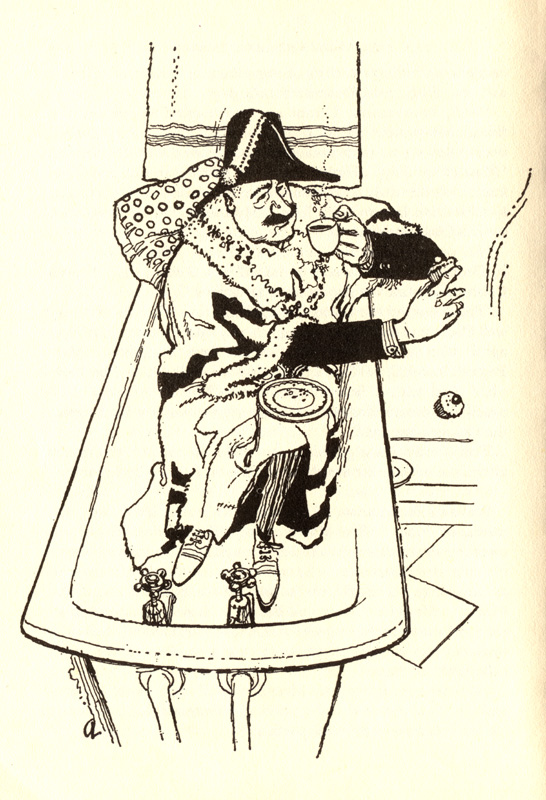

Adamson’s work is, in a sense, much more mundane and ordinary than even Robinson’s. Robinson is, in his “mechanical” work, an artist of ridiculous things. Adamson, though, makes ridiculous things look ordinary. Like, for example, a Mayor having to take his tea in a bathtub:

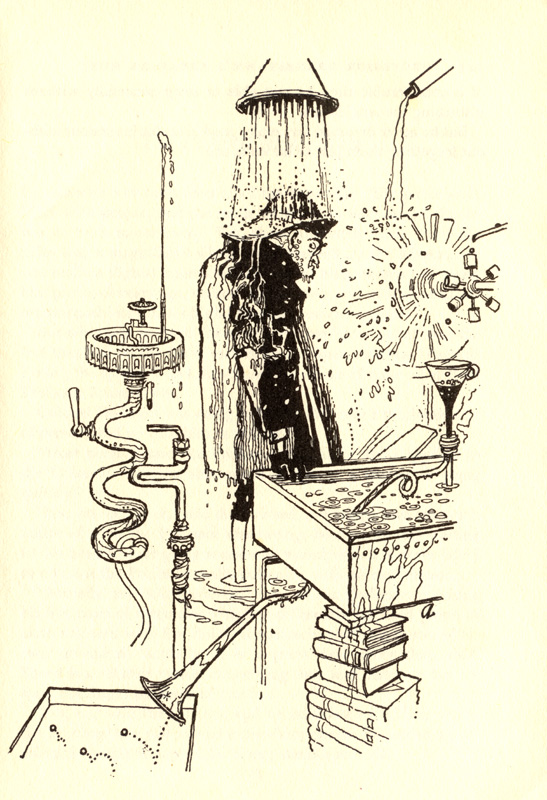

Robinson’s machines look entirely plausible, and their workings are out on show. Adamson’s machinery, though, is hidden away. It’s magical, because you can’t see how it might do what it’s supposed to; it fits Hunter’s descriptions of machines that can do the physically impossible. Some of them are sinister: very 1950s in design, plain cases with the occasional dial or switch, presumably painted grey or pale green. Others are more complicated, but their working is never obvious or spelled out. They are wonderful depictions of machines which never do as they are supposed to.

* not to be confused, of course, with George Adamson

In which it’s time to go home

I’m always sad when a holiday’s over; when it’s time to pack up the tent and drive home again, leaving nothing but a little patch of yellow-white grass behind.

And then back to the office, where little has changed* and I have a big pile of work waiting for me.

* except for the Office Gossip’s resignation

Or, checking in from Devon

Right now I’m sitting on a quayside in Plymouth, in front of some white fluffy clouds, lots of yachts, various “rustic” harbourside buildings, and an Apple Mac. The Mac is nearly as much a holiday as the rest of it: I keep forgetting that British Macs have American-style keyboards, with the ” and @ keys the wrong way around.*

Next week I’m going to be back in the office again, but for now, I’m making the most of the sunshine (by burning slightly) and the free time (by doing nothing much of any importance). Lots of photos when I get back – I really should start using my Flickr account properly.

* to say nothing of §, ~ and |

In which we talk about a classic artist

A few months back, I saw, on a friend’s bookshelf, art books about members of the Robinson family: Charles Robinson and his better-known brother William Heath Robinson; and I resolved to write about them here. It’s taken me a while.

The wonderful thing about Heath Robinson’s work – apart from the army of identikit men who keep his machines running – is that everything looks entirely workable, in a certain sense. Everything looks as if it should fit together and run smoothly, especially with his little arrows and dashed lines to show that this moves that way, that cog turns like so, and the lever over on that side swings round to hit the golf ball over here.

The first place I came across Heath Robinson, though, I found him slightly unsatisfactory. In the 1930s he illustrated two children’s books by writer Norman Hunter, about an absent-minded inventor called Professor Branestawm, a creator of amazing, fantastical, physically impossible inventions. Robinson’s illustrations were just too possible—although they may well have worked, they could never have done everything described in the story. I was, as a child, disappointed. I much preferred his 1970s illustrator—but I’ll tell you about him another time.

In which we know what you’re looking for

deglutation

wemyss bay station

why forests need to be saved – I don’t know, they just do

ravens where to see them in south east england – I’d suggest the Tower, personally

steps of doing long division

computer geekery definition

ball gagged police

why was war between bosnia and serbia – trust me, it’s a long story

gothic and depressive computer desktop backgrounds

goose to blame if i lose my balance

the bad things about solar collectors

splosh fetish

I think that’s enough of that

Or, postcards from Cornwall

It is of course pissing down. We are loitering within tent.

In which we go away for a while

Time for a holiday – the tent’s ready, the car’s all loaded, and we’re going camping. Someone will be looking after the site whilst I’m away, I promise.

The mother was concerned that I wouldn’t be able to see at night. She didn’t think I was taking enough torches. I pointed out I had a small torch, a big torch, a medium torch, a wind-up torch, a strap-to-your-head torch, and an album by “heavy stoner pop” band Torche. That’s enough torches.