Cultural Appropriation

On stories set firmly in a particular place

There are quite a few ideas for blog posts lining up on my pinboard at the moment, and most of them are the sort that require work to write: long, in-depth pieces that need some sort of study or concentration. With the state of things right now, both in the world outside, here at home, and in the office, the space for that level of study and concentration has been a bit hard to come by. However, there’s one thing that has been in my head, on and off, for years, and it’s been sitting in my head for so long that it’s about time I tried to put it into words. It’s about a book which (unlike these) I have read, a much-loved book, one I love myself, in fact, at least at some level. It’s a classic of 1960s YA fiction, particularly in Britain. The Owl Service, by Alan Garner.

If you haven’t read it: it’s a retelling of one of the most famous stories of Welsh mythology, the story of Blodeuwedd, an episode in Math fab Mathonwy, the Fourth Branch of the Mabinogi. I realise, typing that out, that if you’re not already a fan of Welsh mythology all those words in the previous sentence might be so much noise to you. The Mabinogi is a collection of four linked stories, written down in the Middle Ages but presumably somewhat older, which survived in two known manuscript copies;* in the 19th century they were translated into English by the aristocratic philologist Charlotte Guest. Math son of Mathonwy starts with a war between Gwynedd and Dyfed started by a magical pig-theft as a grand distraction from a rather more sordid plan, and traces the threads that follow on from that plan and the destruction and havoc that follows as a result. If it can be said to have a single theme, it’s probably that magic always makes things worse. Blodeuwedd is a woman conjured from flowers to provide a wife for the cursed hero Lleu Llaw Gyffes; she is not particularly a fan of the idea herself, and goes off with another man instead. I won’t tell you the whole story here, but you can probably gather that it isn’t going to end well.

One reason I’m not going to retell the whole story here is that if you haven’t read The Owl Service then you should do; as I’ve said, it’s a modern retelling, bringing the story forward to 1960s Wales and turning it into a triangular relationship between three teenagers: an English girl who has inherited a Welsh country house, her step-brother, and the Welsh son of their housekeeper. The country house is located in an oppressive, narrow valley and the house seems haunted by sounds: motorbikes powering along the road up-valley, and invisible vermin scratching in the roof. As the book progresses there are dark family secrets, mysterious paintings, ghostly reflections, and of course the crockery set of the title. As stories go it is short but dense: there is a lot of information packed into its pages. Garner is very good at offhand description whose significance is not signalled, letting you make the connections yourself later. In the telly adaptation, made by Granada shortly after publication, quite a bit of further exposition had to be added, notably a “story so far” narration at the start of each episode which sometimes describes explicitly events which weren’t really explained or shown at the point they happened.

I must have first read The Owl Service when I was in my early teens, and I know that when I first read it I was already aware that it was an Important Book. I knew this because most children’s novels I recall reading included a few pages of blurb for other novels at the back of the book, and I’d read the blurb for The Owl Service several times in this way before eventually getting a copy of it.** Certainly, much of it went over my head, but I was taken with its description of 1960s Wales; of the valley, lush and green, that almost disappears when you hike uphill to look down from the surrounding mountains; and the combination of kitchen-sink realism and deep mythology, of the idea that all myths did happen, somewhere, in the real world, and that their ghosts still haunt those places. That, though—I came to realise many years later—is where the problem is.

Nowadays I have two translations of the Mabinogi on my bookshelf, although I carefully keep them apart so that we avoid a critical mass of mythology in one place (or more likely, questions on why exactly I need two different translations). If you pick either of them up, and turn to Math fab Mathonwy, you’ll see the story tells you exactly where everything happened. I said earlier there was a war between Gwynedd and Dyfed: it ended when King Pryderi of Dyfed was killed and buried near Maentwrog, just off the A496. The other man that Blodeuwedd went off with was from around Bala; and the key events in the Blodeuwedd story all occurred close to the Afon Cynfal, one of the rivers that flows down into the Vale of Ffestiniog. I know the area well.

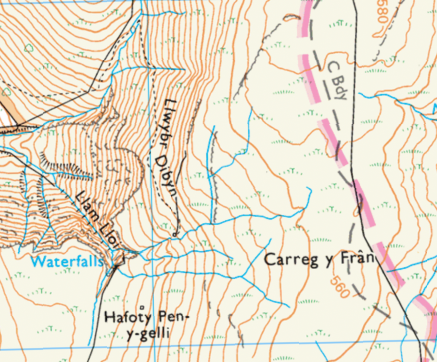

What makes me uncomfortable about The Owl Service is that it’s not set there. It’s not set in some generic imaginary fictional Welsh valley that only exists in Garner’s (and his reader’s) imaginations, either. It’s inspired by a specific place that Garner had visited, Llanymawddwy on the upper Dyfi. If you read the book alongside the Ordnance Survey map of the area, you can track a lot of the walks that the characters take in the book. Garner describes, for example, the walk up to the Ravenstone on the county boundary; and there it is on the map, Carreg y Frân. This is a real place, a real village. But in Garner’s retelling, this is the place the story of Blodeuwedd originally happened, and keeps happening, reoccurring in every generation; when the myth itself is anchored in another real place, an entirely different stretch of the countryside.

Is this cultural appropriation? I’m really not sure; in any case, that’s hardly a well-defined term. Garner certainly tried to put a lot of effort into trying to make his story both realistic and respectful. He learned Welsh to write The Owl Service, but not for vocabulary or to read the myth in the original; rather, he learned it so that he could make the English speech of his Welsh-speaking characters follow Welsh syntax, because he felt that this would be a more respectful way to make them sound Welsh than the superficial technique of dropping random Welsh vocabulary into their statements. In general this works really well, with just one spot where he shows off his erudition to the reader in a slightly clunky way. The feeling I am left with, though, is that he did just come along to Wales and immediately feel as if he had found some deep, spiritual, mythological meaning to the landscape that wasn’t actually there, a meaning that was his own romanticised interpretation of that landscape as filtered through one of the most famous of all the Welsh myths. In a sense this is no different to if he’d travelled half way around the world and felt he had discovered something deep and exciting and mystical there; the only difference is that he’d only travelled a hundred miles or so over the border from Cheshire. The village and the valley in The Owl Service are haunted by the sound of motorbikes, because the road through Llanymawddwy leads to Bwlch y Groes, a steep, high pass that has for many years been well-known in the biking world. I have no doubt the reason motorbikes are important in the plot of The Owl Service is that Garner, visiting Llanymawddwy and exploring the valley, will have frequently seen and heard bikers driving through the village and up the valley towards the pass; will have sat up at Carreg y Frân and heard them roaring in the distance.

Am I the right person to point this out? I’m not Welsh either, after all, and although I’ve spent a lot of time there for one reason and another, I’ve never lived there. I don’t speak the language beyond a few simple phrases like “mae hi’n bwrw glaw” or “dw i wedi yfed cwrw gormod”, although I probably speak no less than most people who live in Wales do. As an English person living in England, are my own attempts to learn Welsh and read Welsh mythology just as appropriative as Garner? Some would probably say so. As someone who spends a fair amount of time in Wales—albeit not as much as I did a few years ago when I commuted over the border every day—it feels like the right thing to do.

The Owl Service is still a fantastic book, despite its flaws, and despite the niggling impression I have that it represents one Englishman’s superficial interpretation of a myth more than it represents the myth itself. In some ways I suspect my biggest disappointment is, as always, that the Good is the enemy of the Perfect. The Owl Service is so embedded in the imagination as the reimagining of the Blodeuwedd story, it seems difficult to believe that any other, potentially better, potentially more Welsh reimagining of it would ever take its place in the canon. Am I just being too much of a perfectionist critic? Maybe so. And the story of Blodeuwedd still exists, and is never going to disappear.

* The bound manuscripts are known as the Red Book of Hergest and the White Book of Rhydderch. This naming pattern clearly chimed with JRR Tolkien, as in his fantasy mythology, The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings were the translations of a set of manuscripts known as the Red Book of Westmarch.

** Incidentally there are still a few classic children’s and YA novels that I only know in this way, from the blurbs in the back of other novels. The Silver Sword is one that springs to mind; or Smith by Leon Garfield.

Home

Home