Just like clockwork (part one)

Time for a building project

Back in the mists of time on Boxing Day, I posted a clue as to what one of my Christmas presents was. A model tram from UGears, which I have been slowly assembling since.

It’s been a fun project, but I’m not completely sure it lives up to the promise on their website that “no glue, special expertise, tools or equipment are required”. With a fair wind and if everything goes well, then maybe. When I opened the box, the kit consisted of:

- Various laser-cut plywood sheets.

- Two rubber bands.

- A small square of fine sandpaper.

- A number of cocktail sticks, individually wrapped.

- A glossy and comprehensive instruction book.

The instruction book is very good and very clear, with each step being shown as a 3D-rendered diagram. However, it starts off listing the extra pieces of equipment you need which aren’t supplied:

- Candle wax, to lubricate the moving parts.

- A knife, to cut some of the cocktail sticks to length.

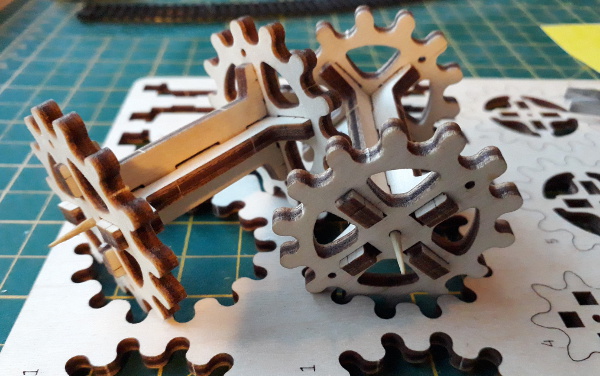

With those to hand, you start off by assembling various gear shafts. Each of these assemblies consists of the gears themselves, four wooden wedges that are inserted through the gear centres, and a cocktail stick that has to be squeezed through a small hole left right in the middle where the four wedges meet.

These are the first ones in the instructions; gears, but also the main “wheels” that the tram sits on. The instructions say the cocktail stick should be inserted symmetrically, with the same length protruding from each end, so it’s very helpful to have a small steel rule to assist with doing it by eye. If the “axle” isn’t symmetrical, a measuring tool is included in the kit to indicate how much the stick should project from one end.

Inserting the cocktail sticks was the first big hurdle. Making the kit in the advised way—assemble the wedges into the gears then slide the cocktail stick down the middle—is very hard to do without accidentally blunting the sharp points at the ends. Unless you’re dealing with one of the gear shafts which needs one or both ends trimming short, this is a problem, because it’s very easy to blunt the sticks to the extent they won’t work any more. I found for most it was easier to assemble the shafts in a slightly different order: take one gear, insert the wedge pieces and the cocktail stick into that gear alone, then squeeze the wedges together at the other end and slide the other gear over the wedges’ clip-shaped ends.

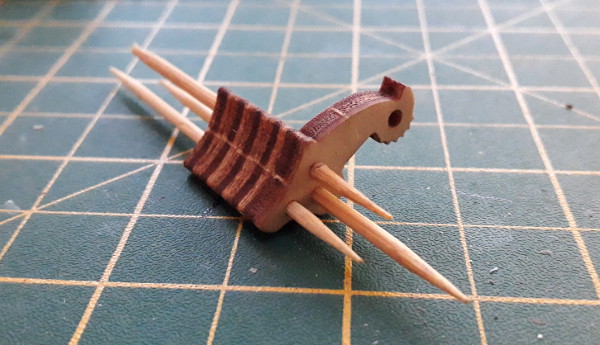

The tolerances of the cocktail sticks don’t help, either. Some parts require sticks to be inserted into holes in the plywood parts, and these are all supposedly a push fit. What quickly became clear is that the cocktail sticks are made to rather looser tolerances than the laser-cut parts: some sticks will be a reasonable push-fit in the holes, and some will have no chance of going in. With these parts, I ended up picking which stick I was going to use, then opening out the hole with a broach to fit. If I went a bit too far and made it a sliding fit, I used a little dab of Resin W to glue the stick in place.

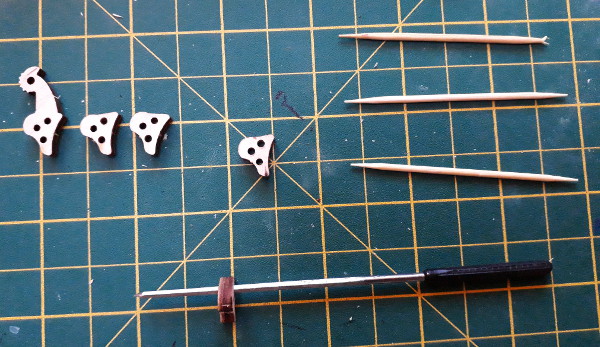

You can see this under way with these parts for the pawl which holds the “rubber band shaft” tight after it’s been wound. You can also see that here I’m reusing a cocktail stick whose end I have already wrecked, in a position where it will be trimmed off short. As the lowest of the three holes in each pawl piece is rather close to the edge, I found one of the narrower sticks in the kit for that position, so it wouldn’t need opening out at all. You can clearly see the different widths of the supplied cocktail sticks, and on the right-hand pawl piece you can see how much I’ve had to open out the uppermost hole, compared to the unmodified bottom hole, in order for the fat stick at the top to be a push fit into it. Using a broach for this, it’s easy to roughly remember how much of the broach’s cutting length is needed to get the hole to around the right width before you start testing for fit.

Once the parts were pushed onto the sticks, the ends of two could be trimmed off, leaving a single shaft for it to pivot on.

Building all the various gears and related parts took quite a few hours, so it was rather pleasing how easily the main framework of the tram fitted together, and how straightforward it was to slip the ends of each shaft into their appropriate hole in the frames. It was rather pleasing, too, to find how well the initial gear chain rotated. It links the wheels together, and also includes a shaft which seems to be in there purely to make a clicking noise.

You might notice that the pawl from the previous photos hasn’t been fitted to the main assembly yet. That comes later, and was a little bit more fiddly. We’ll come on to that another time.

To be continued.

Home

Home